In utero MRI does not need to replace ultrasound as the modality of choice to evaluate fetal brain development, despite MRI's ability to catch a few more potential abnormalities, according to a study set for publication in the July issue of Clinical Radiology.

In a comparison of more than 200 fetuses in their second or third trimester, in utero MRI detected two suspicious anomalies missed by ultrasound, which still achieved a negative predictive value (NPV) of 99.5%.

"One important implication of this finding is ultrasound might fail to detect some brain abnormalities during screening," wrote lead author Paul Griffiths, PhD, and colleagues at University of Sheffield in the U.K. "This study shows that this does not occur at high frequency and supports ultrasound being the primary screening method for brain imaging. In utero MRI should be used as an adjunct to ultrasound only when brain abnormalities are suspected on ultrasound in low-risk pregnancies."

Previous research has shown that in utero MRI does improve diagnostic accuracy when clinicians suspect a brain abnormality on ultrasound. Those studies, however, did not investigate the efficacy of in utero MRI when no such brain abnormality was detected or suspected on ultrasound.

"The intrinsic value of a diagnostic test relies not only on its ability to identify an abnormality correctly when one is present, but also to exclude abnormalities correctly when they are not present," the authors wrote. "To date, studies of in utero MRI for fetal brain abnormality have been undertaken among fetuses in which a brain abnormality was suspected (predominantly on the basis of abnormal ultrasound) and, although these strongly support the use of in utero MRI in such cases, the benefit, if any, of in utero MRI in ostensibly normal pregnancies is unknown."

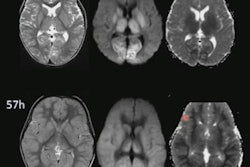

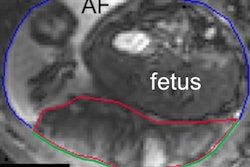

Griffiths and colleagues recruited 198 pregnant women (mean age 31.5 years; range, 20-46 years) who were carrying 205 fetuses (seven women had twins) from 12 centers across the U.K. The subjects underwent in utero MRI scans on either a 1.5-tesla whole-body system (Signa HDx, GE Healthcare) or a 3-tesla scanner (Ingenia, Philips Healthcare) (Clin Radiol, July 2019, Vol. 74:7, pp. 527-533).

"The accuracy of a negative ultrasound was quantified by the NPV, the percentage of fetuses in whom no abnormality was subsequently detected," the authors explained. "For in utero MRI, NPV agreement was derived separately for fetuses whose initial ultrasound was normal and abnormal ultrasound."

In viewing the imaging results from both modalities, ultrasound reached an NPV of 99.5%, compared with 100% for in utero MRI for normal-risk pregnancies. The difference was that in utero MRI identified two cases of ventriculomegaly among the 205 fetuses. Ventriculomegaly is a condition whereby cerebrospinal fluid-filled structures in the brain become larger than normal and consequently could adversely affect brain development.

Given the scant separation in performance between the two modalities, Griffiths and colleagues concluded that the findings confirm the "validity of ultrasound remaining as the primary screening imaging method for pregnancy, and further support the need for additional in utero MRI when abnormalities are detected on ultrasound; however, further research on fetuses at an increased risk of brain abnormality may be appropriate."