Researchers using MRI to study blood flow through the placenta discovered a new type of contraction during pregnancy. The authors described the characteristics of the aptly named "utero-placental pump" in a study published on May 28 in PLOS Biology.

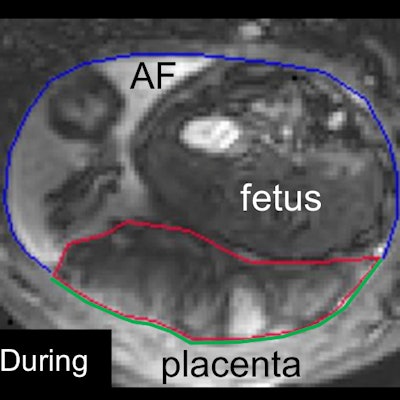

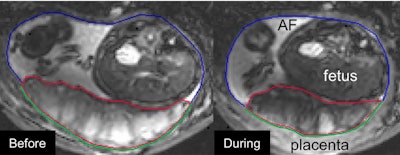

During a utero-placental pump contraction, the placenta and uterine wall contract independently of the uterus, which differs from the well-known Braxton-Hicks contractions that involve the entire uterus. The authors hypothesized that the mechanism helps facilitate blood flow through the placenta and fetus.

The relaxed placenta before the utero-placental pump contraction (left) and during the contraction (right). The placenta is the area surrounded by the red line. Image courtesy of Neele Dellschaft, PhD, and the University of Nottingham.

The relaxed placenta before the utero-placental pump contraction (left) and during the contraction (right). The placenta is the area surrounded by the red line. Image courtesy of Neele Dellschaft, PhD, and the University of Nottingham."We now want to work out the purpose of these contractions, but we think it might be to stop blood stagnating in parts of the placenta," stated lead study author Neele Dellschaft, PhD, a research fellow at the University of Nottingham School of Physics and Astronomy in England, in a press release.

During pregnancy, maternal blood flows through the placenta, enabling oxygen exchange between the mother and fetus. Previous mathematical modeling suggested a contraction might aid in this process, but contractions of the placenta haven't been well studied.

For the current study, the authors used a wide-bore MRI scanner to investigate placental blood movement and oxygenation differences between 34 women with healthy pregnancies and 13 women with preeclampsia, a complication characterized by high blood pressure and signs of organ damage.

MRI revealed that in healthy pregnancies, maternal blood flow was visualized as it moved from the uterine wall and through the placenta, then sped up again as it exited the system. The slow blood flow rate in the middle of the process helps to deliver sufficient oxygen to the fetus, the authors noted.

But in pregnancies with preeclampsia, the arterial structures of the placenta appeared altered and blood flowed faster through the entire system. The faster blood flow resulted in lower placental oxygenation and more varied oxygenation for pregnancies with preeclampsia.

However, what truly surprised the authors was a placental-uterine contraction that occurred during a 10-minute timespan for 19 of the women in the study, including 35% of women with normal pregnancies and 70% with preeclampsia.

The so-called utero-placental pump reduced the area and thickness of the myometrium that underlies the placenta. It also stretched the rest of the uterine wall and reduced placental volume by up to 40%.

The authors don't know why they observed the contraction in a greater proportion of women with preeclampsia, nor do they know what happens to oxygenation and blood flow before, during, or after the pump occurs. However, they believe that future study of the pump could reveal further differences between placentas in healthy and preeclampsia pregnancies.

"The shape of the healthy placenta during contraction is similar to the thickened shape of the compromised placentas, raising the possibility that the preeclamptic placenta is permanently contracted to some extent," the authors wrote.