Researchers at the National Institutes of Health (NIH) have found that high levels of particulate air pollution are tied to increased breast cancer incidence.

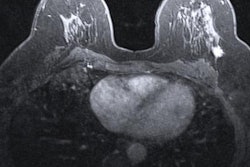

Researchers led by Alexandra White, PhD, head of the Environment and Cancer Epidemiology Group at the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS), reported significant increases in breast cancer incidence among women who on average had higher particulate matter levels (2.5 microns) near their home prior to enrolling in the study. The results were published September 11 in the Journal of the National Cancer Institute.

The study was conducted by researchers at the NIEHS and the National Cancer Institute (NCI), both part of NIH.

White and colleagues explored the effects of particulate matter, a mixture of solid particles and liquid droplets found in the air, on women's health. This matter comes from numerous sources, such as motor vehicle exhaust, combustion processes, wood smoke and vegetation burning, and industrial emissions. The particulate matter pollution measured in this study was 2.5 microns in diameter or smaller. This is small enough to be inhaled deep into the lungs.

The researchers conducted their study using information from the NIH-AARP Diet and Health Study, which enrolled more than 500,000 men and women between 1995 and 1996 in six states and two metropolitan areas. The women in the cohort were on average about 62 years of age and most identified as being non-Hispanic white. They were followed for about 20 years, during which 15,870 breast cancer cases were identified. The team reported an 8% increase in breast cancer incidence for living in areas with higher than 2.5 microns of exposure.

The authors called for future studies to explore how the regional differences in air pollution, including the various types of particulate matter that women are exposed to, could impact a woman's risk of developing breast cancer.