Structural MRI could help clinicians identify chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE) in living individuals -- a feat that hasn't really been possible up to now, according to a study published December 7 in Alzheimer's Research & Therapy.

"MRI is commonly used to diagnose progressive brain diseases that are similar to CTE such as Alzheimer's disease," lead author Michael Alosco, PhD, of Boston University School of Medicine said in a statement released by the university. "Findings from this study show us what we can expect to see on MRI in CTE. This is very exciting because it brings us that much closer to detecting CTE in living people."

CTE is a neurodegenerative condition associated with repetitive impacts to the head and thus most often found in contact sport athletes, soldiers, and victims of physical abuse. Until now, clinicians haven't been able to diagnose the disease in living patients but only through autopsy, the team wrote. And although PET imaging and cerebrospinal fluid protein analysis may be useful for diagnosing CTE in living persons, they are still under investigation for this purpose and could be compromised by high cost and invasiveness. That's where structural MRI could come in, the group explained.

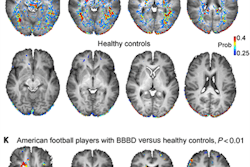

Alosco's team assessed CTE patterns on MRI by comparing structural features from exams taken from 55 men before death and autopsy confirmation results of CTE after death (52 of the 55 men had participated in American football across a range of ages and levels). The main reason the men underwent MRI was for dementia of neurogenerative disease-related symptoms (65%).

These exams were then compared with those of 31 men who had normal cognition when the MRI was performed (the most common indication for MRI in this cohort was cerebrovascular symptoms, followed by memory complaints).

The group found that the MRI exams performed on living patients at risk of CTE showed more severe frontal and temporal lobe atrophy, medial temporal lobe atrophy, lateral and third ventricular enlargement, and higher rates of a cavum septum pellucidum (CSP) compared to their healthy counterparts -- in fact, the odds for a CSP were 6.7 times higher in brain donors with CTE than those without the disease. The study also found that more severe p-tau pathology at autopsy was connected to higher rates of atrophy on MRI exam among brain donors with CTE.

"[Our study provides], for the first time, insight into the structural MRI profiles of people with neuropathologically confirmed CTE, as well as support p-tau accumulation as a correlate of atrophy in CTE," the group wrote.

More research is needed, said corresponding author Dr. Jesse Mez, director of Boston University's Alzheimer's Disease Center Clinical Core in the statement.

"While this finding is not yet ready for the clinic, it shows we are making rapid progress, and we encourage patients and families to continue to participate in research so we can find answers even faster," Mez said.