Using arterial spin labeling (ASL) MRI, researchers have found that increased cerebral blood flow in children and young adults with chronic kidney disease correlates with subsequent decreased cognitive function, according to a study published online June 12 in Radiology.

The highest levels of increased blood flow were observed in the brain's default network, which becomes more active when a person is not focused on a particular task. The finding runs counter to the current belief that decreased blood flow is a primary cause of cognitive decline.

"One of the main findings is that there are certain regions of the brain where the blood flow in chronic kidney disease patients remains elevated even after we correct for anemia and hypertension," said senior author Dr. John Detre, a professor of neurology and radiology and director of the Center for Functional Neuroimaging at the University of Pennsylvania. "The extent of the increases seems to correlate with the patients' cognitive performance deficits. In other words, the more abnormal the blood flow was, the worse the cognition was."

Domino effect

Dr. John Detre from the University of Pennsylvania.

Dr. John Detre from the University of Pennsylvania.It is well-known that chronic kidney disease in adults can cause myriad health issues. The problems begin with high blood pressure, which in turn leads to lesions in the brain. These scars ultimately can lead to deteriorating cognitive function in older patients. While chronic kidney disease also causes high blood pressure in children and young adults, these patients, for the most part, are not old enough to have formed brain lesions.

"So studying this population gives us a kind of cleaner way to understand what kidney function is doing to the brain without worrying if what we are looking at is the effects of hypertension on the brain," Detre explained.

ASL-MRI has long been the primary MRI technique to measure blood flow in the brain. In fact, Detre was among the early developers of the arterial spin labeling method in the early 1990s.

"We have been applying it in a variety of neurological and psychological disorders. There are certain features of this method that are very appealing for studies like this," Detre told AuntMinnie.com. "First of all, arterial spin labeling can quantify cerebral blood flow to measure regional brain activities. The ability to quantify regional brain activity in this study is primarily a way of mapping out brain activity differences between the patients and the controls."

While there have been previous studies on the cognitive capabilities of children with chronic kidney disease, this project, launched by co-author Dr. Susan Firth, PhD, a pediatric nephrologist at the University of Pennsylvania, added MRI to the investigation to understand what was going on in the brain to cause cognitive deficits.

Key indicators

For this study, the researchers enrolled 73 patients ages 8 to 25 years (mean age, 15.8 ± 3.6 years) with stage II, III, or IV chronic kidney disease between August 2011 and October 2014, along with 57 age-matched control subjects (Radiology, June 12, 2018).

Subjects underwent whole-body 3-tesla MRI scans (Magnetom Verio, Siemens Healthineers) with an eight-channel receive-only head coil and body coil. Resting cerebral blood-flow measurements were acquired using ASL with a 2D gradient-echo echo-planar imaging sequence.

The researchers then combined ASL-MR images with a subject's hematocrit level to determine the differences in cerebral blood flow between the young patients with chronic kidney disease and the healthy control subjects. Hematocrit level refers to the percentage of red cells in the blood, compared with the total volume of blood.

"Hematocrit is a well-known modulator of cerebral blood flow, and chronic kidney disease is associated with anemia due to a decrease in erythropoietin production," the authors wrote.

To round out the study, the subjects were asked to perform a series of neurocognitive tests that featured age-specific standardized assessments for intellectual and executive functions, attention span, memory, and visual spatial processing.

Cognitive contributors

In reviewing the data, the researchers found that hematocrit levels were significantly lower in patients with chronic kidney disease than in the control subjects. There also was a significant difference between these two groups in systolic and diastolic blood pressure, which affects cerebral blood flow.

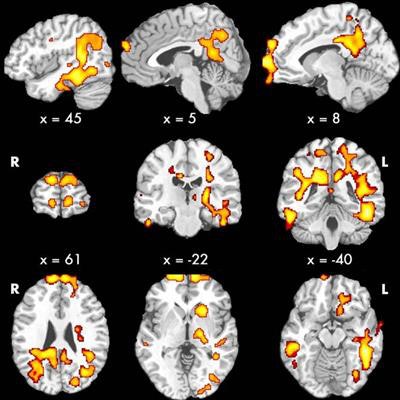

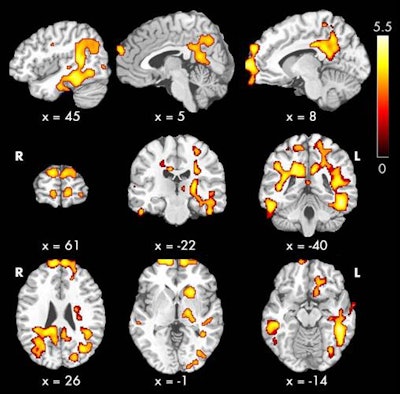

When the researchers excluded hematocrit levels, age, and gender, they found clusters of increased cerebral blood flow in several regions of the brain among patients with chronic kidney disease compared to healthy controls. The differences were most apparent in the bilateral prefrontal cortices, middle and inferior temporal cortices, posterior cingulate cortex, precuneus, left hippocampus, striatum, and thalamus. This network of brain regions becomes active when a person is not focused on a particular task.

In particular, patients with chronic kidney disease had higher global cerebral blood flow than the control subjects, as well as higher flow in gray and white matter.

| Blood-flow changes on ASL-MRI in patients with chronic kidney disease | ||

| Control subjects | Patients with chronic kidney disease | |

| Mean global cerebral blood flow | 56.5 mL/100 g/min | 60.2 mL/100 g/min |

| Mean gray-matter blood flow | 66.5 mL/100 g/min | 71.0 mL/100 g/min |

| Mean white-matter blood flow | 30.7 mL/100 g/min | 31.8 mL/100 g/min |

ASL-MRI maps show regions of the brain in which cerebral blood flow was greater in patients with chronic kidney disease than normal subjects. The areas (red, yellow, and orange) are associated with cognitive function. Image courtesy of Radiology and RSNA.

ASL-MRI maps show regions of the brain in which cerebral blood flow was greater in patients with chronic kidney disease than normal subjects. The areas (red, yellow, and orange) are associated with cognitive function. Image courtesy of Radiology and RSNA.In addition, there were no brain regions in which the control subjects showed significantly higher cerebral blood flow than the patients with chronic kidney disease.

"Our interpretation is that these blood-flow maps of regional brain function after correcting for anemia can be a biomarker of the cognitive dysfunction," Detre said.

Contradictory findings

Interestingly, the discovery of a correlation between increased blood flow in the brain and poorer cognitive performance contradicts current knowledge that reduced blood flow is one primary cause of subpar cognition. The researchers speculated about a couple of reasons for this finding.

It may be an indication of hyperactivity, in which the brain works harder to maintain performance, Detre said. Another possibility is a disturbance in the regulation of blood flow in these patients.

Currently, there are no definitive plans to follow up on this study; however, Detre said it would be interesting to follow patients with chronic kidney disease to see if any of these measures can predict outcomes.

"It also would be very interesting to get longitudinal data where we can follow the same people as their kidney disease worsens as they grow older or if there are associated medical problems, and try to understand how to fix regional brain function," he said. "Whether those studies will occur will depend on the availability of funding."