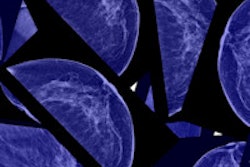

A new research study published online July 6 in JAMA Internal Medicine is again questioning the effectiveness of widespread breast screening. Mammography screening of the general U.S. population mostly just produces overdiagnosis, with no measurable effect on mortality, according to the researchers.

A multicenter group that included mammography skeptic Dr. Gilbert Welch of Dartmouth College performed an observational study of 16 million women who were at least 40 years old. The subjects received mammography screening in 2000, and the researchers followed the population for 10 years. They calculated breast cancer incidence and breast cancer-related mortality over the study period, reporting the results on a county-by-county basis.

Welch and colleagues found that rising rates of screening produced more breast cancer diagnoses, particularly of smaller cancers, but death rates from breast cancer remained the same. The findings indicate that widespread breast screening is ineffective and should be replaced by a program in which screening is more directed to individuals who are at high risk of breast cancer, according to the authors (JAMA IM, July 6, 2015).

The study is drawing fire from proponents of mammography, however, who are criticizing its design, in particular its application of population-based findings to individual women.

Earlier work

Welch first raised hackles in the mammography community in November 2012, with the publication of a study in the New England Journal of Medicine that claimed that screening mammography has only marginally reduced the rate at which women present with advanced cancer. While the death rate from breast cancer had fallen 30% since the 1970s, screening only made a small contribution to this reduction, and nearly one-third of all newly detected breast cancers are actually cases of overdiagnosis, in which the cancer would never pose a health threat during a woman's lifetime, the researchers claimed.

In the current paper, the issue was revisited by lead author Charles Harding, who is with a private practice in Seattle, and senior author Richard Wilson, PhD, of Harvard University, along with Welch. They noted that county-level data on rates of mammography screening and breast cancer diagnosis are available for one-quarter of the U.S. population. They decided to use this information to assess the relationship between screening mammography as it's currently practiced and breast cancer incidence, tumor size, and breast cancer mortality.

The researchers started with data from nearly all U.S. counties (547 in all) that had been reported to the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database from January to December 2000. A total of 16,120,349 women 40 years or older were included; elderly women were not excluded. The median mammography compliance rate over the last two years was 62.2% across all counties.

Among all the counties reporting, 55,809 women at least 40 years of age were diagnosed with breast cancer in 2000; follow-up data were available for 95.3%, or 53,207 women. The authors noted that fewer deaths were attributed to breast cancer (7,729) than to other causes (10,511).

The researchers first compared the extent of screening mammography with breast cancer incidence and found a clear correlation (weighted r = 0.54, p < 0.001). Indeed, a 10-percentage-point increase in screening compliance at the county level was associated with a 16% increase in breast cancer incidence. But they found no evidence of a relationship between the extent of screening and 10-year breast cancer mortality (weighted r = 0.00, p = 0.98).

They also investigated whether screening was resulting in fewer aggressive surgical procedures, another perceived benefit of screening, as cancers are thought to be found at an earlier stage. While a 10-percentage-point increase in the screening compliance rate corresponded to more breast-conserving procedures (relative rate of 1.24), there was no corresponding reduction in procedures such as total and radical mastectomies.

"Across U.S. counties, the data show that the extent of screening mammography is indeed associated with an increased incidence of small cancers but not with decreased incidence of larger cancers or significant differences in mortality," the authors wrote.

Overdiagnosis at work?

The researchers believe overdiagnosis is behind their findings, which echo other studies with high rates of early-stage breast cancer.

"What explains the observed data?" the researchers wrote. "The simplest explanation is widespread overdiagnosis, which increases the incidence of small cancers without changing mortality, and therefore matches every feature of the observed data."

The results are drawing criticism, however. Dr. Daniel Kopans of Harvard University and Massachusetts General Hospital noted the researchers' use of an ecological study -- a type of observational trial that looks at data at the population level -- to infer relationships among individuals in the study cohort. Indeed, the researchers warned of this drawback -- called the "ecological fallacy" -- in their paper.

"There is a reason why statisticians warn of the 'ecological fallacy,' " Kopans wrote in an email to AuntMinnie.com. "The 'fallacy' to which they refer is inferring from the observations of groups the results for individuals without any proof (cause and effect) that these inferences have any validity. It is entirely possible that the authors could have looked at car sales and come to similar conclusions about their relationship to breast cancer."

For the full text of Kopans' comments, click here.

In their conclusion, Harding et al pointed out that while they believe the study suggests screening directed at the general U.S. population mostly results in overdiagnosis, they are not calling for the cessation of all breast screening.

"The balance of benefits and harms is likely to be most favorable when screening is directed to those at high risk, provided neither too frequently nor too rarely, and sometimes followed by watchful waiting instead of immediate active treatment," they wrote.