A new study of female rugby players suggests that contact sports can produce long-term brain changes visible on MRI scans -- even if players don't experience concussion, according to a study published June 17 in Neurology.

The findings confirm that contact sports can have far-reaching effects on the brain, lead author Ravi Menon, PhD, of Western University in London, Canada, said in a statement released by the American Academy of Neurology (AAN).

"There's no longer a debate that when an athlete is diagnosed with a concussion caused by a sharp blow or a fall, there is a chance it may contribute to brain changes that could either be temporary or permanent," Menon said. "But what are the effects of the smaller jolts and impacts that come with playing a contact sport? Our study found they may lead to subtle changes in the brains of otherwise healthy, symptom-free athletes."

To investigate the effect of contact sports over time on athletes' brains, Menon and colleagues conducted a study that included 101 female college players, 70 who played rugby and 31 who were rowers or swimmers. All were concussion-free six months before the study started and for the duration of the research, although some of the rugby players had histories of concussion before the six-month prestudy period. (None of the noncontact sport athletes had histories of concussion.)

Of the 101 athletes, 37 rugby players and nine rowers wore devices that recorded head impacts equal to or greater than 15 grams as part of the study. Rowers did not experience any impacts, but 70% of the rugby players experienced an average of three impacts during two practices and one preseason game.

| Number of head impacts in female college rugby players | ||

| Type of impact | Number of impacts exceeding 15 grams | Average number of impacts per athlete |

| During game | 36 | 1 |

| During two practices | 115 | 2 |

| Total | 151 | 3 |

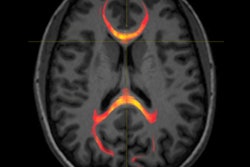

Using MRI, the authors scanned the brains of the study cohort during in- and offseason play, examining how water molecules moved through the white brain matter of the athletes to identify any brain changes.

The MRI scans of rugby players' brains showed changes in nerve fibers that connect areas of the brain responsible for fear, pleasure, and anger, as well as changes to how the brain communicates among areas that control memory and visual processing; in some of the players, these changes progressed over time. The researchers found no such changes in the brains of the swimmers or rowers.

The effects of undetected impacts to the brain stack up over a full sports season and years of offseason play and should be investigated further, Menon and colleagues concluded.

"Even with no concussions, the repetitive impacts experienced by the rugby players clearly had effects on the brain," Menon said in the AAN statement. "More research is needed to understand what these changes may mean and to what extent they reflect how the brain compensates for the injuries, repairs itself or degenerates so we can better understand the long-term health effects of playing a contact sport."