Researchers from New York University (NYU) have developed a unique MRI-based approach for better evaluating damage from concussions that uses measurements of water diffusion to obtain a microscopic view of the brain's white matter, according to a study presented Tuesday at RSNA 2019.

More specifically, the MR images show how the corpus callosum, which contains nerve fibers that carry signals between the brain's left and right hemispheres, is vulnerable to damage from a mild traumatic brain injury. When the concussion occurs, it disrupts the signals between the brain's two hemispheres.

"Looking at how water molecules are diffusing in the nerve fibers in the corpus callosum and within the microenvironment around the nerve fibers allows us to better understand the white matter microstructural injury that occurs," said study co-author Dr. Melanie Wegener, resident physician at NYU Langone Health.

For this study, Wegener and colleagues used 3-tesla MRI scans (Skyra, Siemens Healthineers) to compare the corpus callosum in 36 patients (mean age, 36 years) within one month of their injury to the same images from 27 healthy controls (mean age, 37 years). The water diffusion findings then were combined with the test results from a test developed by Wegener and colleagues at NYU Langone called the Interhemispheric Speed of Processing Task.

In the test, subjects sit in a chair and focus on the letter X, which is displayed on a screen directly in front of them. The researchers then flash three-letter words to the right or the left of the X and ask the participants to say those words as quickly as possible. By doing so, the researchers can determine the reaction times of concussed patients, compared with healthy controls.

"There is a definite and reproducible delay in reaction time to the words presented to the left of the X, compared with words presented to the right visual field," Wegener explained. "This shows it takes time for information to cross the corpus callosum from one hemisphere to the other, which is measured by the difference in response time between words presented to different sides of our visual field."

NYU researchers suggest that the delay is likely due to the fact that language function is most often located in the left hemisphere, which means information presented to the left visual field is first transmitted to the right visual cortex in the brain and then has to cross over the corpus callosum to get to the left language center. In contrast, words that are presented to the right visual field do not need to cross the corpus callosum.

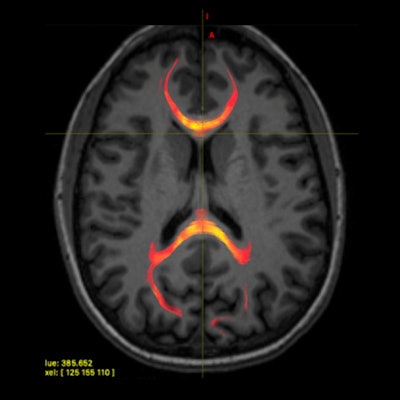

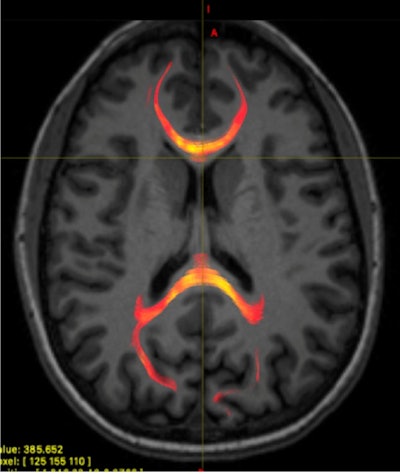

MR image from a patient with mild traumatic brain injury demonstrating corpus callosum fiber tractography, which is a 3D reconstruction of white-matter fibers. This image specifically provides information on the axonal water fraction. Image courtesy of the RSNA.

MR image from a patient with mild traumatic brain injury demonstrating corpus callosum fiber tractography, which is a 3D reconstruction of white-matter fibers. This image specifically provides information on the axonal water fraction. Image courtesy of the RSNA.Most importantly, reaction time results among the healthy controls corresponded with several diffusion measures in the splenium, an area of the corpus callosum located between the right visual cortex and the left language center. There was no such correlation in the patients with concussions, which would suggest microstructural changes occurred because of the concussions.

As for the clinical ramifications of the findings, Wegener and colleagues suggested that patients could undergo an MRI scan right after a concussion to determine if there is any injury to the white matter of the brain and undergo early treatment, if necessary.

"Another thing we can do is use MRI to look at patients' brains during treatment and monitor the microstructure to see if there is a treatment-related response," she added.