The use of neuroimaging in infants being assessed for abuse varies by hospital -- and by insurance type, an indication of healthcare disparities, according to a study published April 20 in JAMA Network Open.

The results suggest that there's room for improvement when it comes to evaluating children for abuse, since variations in neuroimaging assessment may be a sign of bias, wrote a team led by Dr. Katherine Henry of the Children's Hospital of Philadelphia.

"[We] found that performance of neuroimaging varied substantially across hospitals, despite adjustment for case mix and temporal trends," the group noted. "These findings suggest opportunities for quality, safety, and equity improvement."

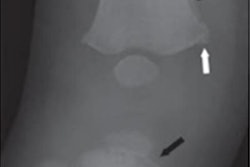

Infants who present with injuries suspicious for abuse -- such as fractures -- may appear neurologically healthy but have injuries such as subdural hematomas that aren't apparent, the group noted. The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends neuroimaging with CT or MRI in infants with "suspicious bruising," "skeletal injuries associated with shaking or impact," or "fractures suspicious for abuse."

But guidelines as to when neuroimaging is appropriate in abuse cases could be clearer, especially since the benefit must be weighed against radiation exposure.

"Given the importance of detecting occult intracranial injuries, complexity of the decision to perform neuroimaging, and lack of clear practice guidelines, overassessment and underassessment may be occurring," Henry and colleagues wrote. "If evidence of excess variation in neuroimaging practices when abuse is suspected were found, this would support the need for quality and safety improvement."

Henry's group investigated neuroimaging practice variations among 44 U.S. children's hospitals for infants with fractures evaluated for abuse, taking into consideration factors associated with potential bias such as insurance type and race/ethnicity. The study included 1,549 children younger than 12 months with a femur or humerus fracture (or both) but with no signs of head injury; median age was six months. The fractures prompted the children to be evaluated for abuse via neuroimaging with CT or MRI.

Most of the children were white (44.4%), while 28.9% were Black, and 16.5% were Latinx. The team found the following factors increased the likelihood that a child would undergo neuroimaging:

- Younger age (0 to 3 months)

- Fracture type (femur and humerus fracture)

- Hospital setting

- Public insurance

Previous research has suggested that there's variation in skeletal evaluations of children who are suspected of being abused, and this variation would therefore lead to discrepancies in neuroimaging incidence, since neuroimaging is prompted by skeletal injuries. This study found that 59.9% of infants younger than 12 months with a femur or humerus fracture underwent neuroimaging, but there was a range of neuroimaging use among hospitals of 37.4% to 83.6%.

"Our data suggest that with current neuroimaging guidance, clinicians across different children's hospitals took disparate approaches to neuroimaging," the team wrote. "In addition, our study findings suggest that biases based on patient demographics may be associated with imaging decisions."