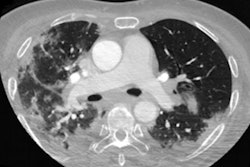

CT angiography (CTA) is an effective initial imaging exam for determining the source of bleeding in the head or neck and offers a noninvasive way to assess next steps for treatment, according to research published August 5 in Emergency Radiology.

If conservative treatment measures for acute head and neck bleeding fail, patients may undergo digital subtraction angiography (DSA) to localize the bleeding source before endovascular treatment. But both DSA and endovascular treatment come with hazards, wrote a team led by Dr. Michael Travis Caton Jr. of Brigham and Women's Hospital and Harvard Medical School, both in Boston. That's why CTA could help.

"Noninvasive preprocedural imaging is desirable both to expedite therapy and conceivably avoid complications and risk of DSA if no target lesion is identified," the group wrote.

Life-threatening

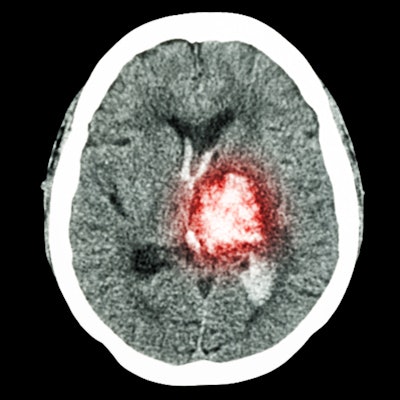

Acute hemorrhage in the head and neck is a life-threatening condition, as it can lead to asphyxiation and hemorrhagic shock, the authors noted. CTA has long been used to locate bleeding and plan endovascular therapy procedures for gastrointestinal hemorrhage, but its value as a tool for this kind of treatment planning for acute hemorrhage in the head and neck remains unclear.

"Whether CTA plays a role in the workup of patients presenting with [acute hemorrhage in the head and neck] is not established," the team wrote. "We sought to investigate the role of CTA by comparing the findings of CTA and DSA with corresponding endovascular treatment results in this patient population."

The study included 30 CTA exams performed in 18 patients with acute hemorrhage in the head and neck between June 2015 and October 2018. The researchers documented DSA and endovascular therapy findings.

Of the 30 exams, 11 (36.7%) prompted DSA follow-up within 24 hours. The majority of bleeding was caused by malignancies (61.1%); in fact, all 11 of these exams were from patients who had undergone chemotherapy or radiotherapy.

CTA identified sources of bleeding in 23.3% of the exams; seven of seven patients with definite or possible source of bleeding on CTA had DSA and four of 23 patients with negative CTA exams underwent DSA.

| CTA findings for acute head and neck hemorrhage and implications for treatment | ||

| CTA findings | DSA performed | Endovascular treatment performed |

| Positive overall:

7 of 30 (23.3%) |

7 of 7 (100%) | 6 of 7 (85.7%) |

| Positive definite:

3 of 30 (10%) |

3 of 3 (100%) | 3 of 3 (100%) |

| Positive possible:

4 of 30 (13.3%) |

4 of 4 (100%) | 3 of 4 (75%) |

| Negative:

23 of 30 (76.7%) |

4 of 23 (23.3%) | 4 of 4 (100%) |

Using DSA as the gold standard, the team found CTA had a sensitivity of 70% and a specificity of 100%.

| CTA performance regarding negative DSA for acute head and neck bleeding | |

| Performance measure | For negative DSA |

| Sensitivity | 70% |

| Specificity | 100% |

| Accuracy | 72.7% |

| Positive predictive value | 100% |

| Negative predictive value | 25% |

Why did some of the patients negative for bleeding findings on CTA still undergo endovascular treatment? Because head and neck bleeding is tricky to manage, the authors noted.

"It is likely that patients in the CTA-negative group who were taken to angiography had ongoing or refractory symptoms following DSA; new or recurrent bleeding after negative CTA is entirely plausible," the group wrote. "Although many patients ... were effectively precluded from angiography after negative CTA, patients in this group have a guarded prognosis and should be monitored with the understanding that they may rehemorrhage."

Less invasive assessment

The study results offer clinicians and patients a less invasive way to discern cause and location of head and neck bleeding, according to the authors.

"The use of noninvasive imaging, like CTA, as a screening tool [for conditions like head and neck cancer] could conceivably reduce the need for urgent catheter angiography and its associated procedural risks, including stroke, access-site complications, and arterial dissection," the group wrote. "Proper patient selection will require further study in larger patient cohorts, allowing for adequate control of individual patient risk factors. Such studies will clarify low-risk patients, in whom observation and conservative care would be appropriate, versus high-risk patients with potential for rapid decompensation, in whom direct triage to angiography would be the best option."

The bottom line? It's safe to add CTA to the clinical toolkit for handling acute head and neck bleeding, according to the authors.

"CTA has high specificity and reasonable sensitivity for detecting arterial source of bleeding in patients presenting with acute hemorrhage in the head and neck," they concluded. "Patients with negative CTA may avoid catheter angiography in most cases; however, false-negative CTA should not preclude angiography in high-risk patients."