A new radiomics technique can determine which lung cancer patients will benefit from immunotherapy by analyzing the texture, volume, and shape of lesions on chest CT scans, according to a study published online November 12 in Cancer Immunology Research.

The group, led by Anant Madabhushi, PhD, of Case Western Reserve University, developed the radiomics technique, called DelRADx, to facilitate decision-making regarding treatment for lung cancer patients. The technique relies on a machine-learning algorithm that can evaluate changes on the CT scans of lung cancer patients over time.

Currently, about one-fifth of patients actually respond to expensive immunotherapies such as immune checkpoint inhibitors that help the immune system to fight cancer. It is generally only after two to three cycles of immunotherapy that clinicians can determine whether the treatment was effective by examining changes to the size of lesions on CT scans.

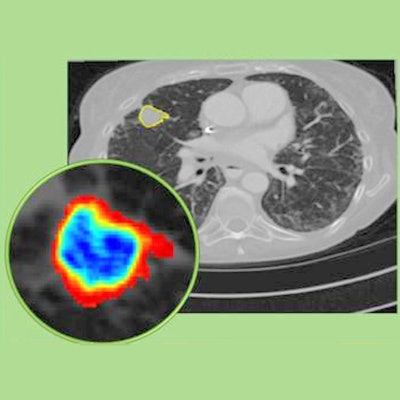

In contrast, the Case Western group's machine-learning algorithm was able to determine a patient's likely response to immunotherapy by analyzing the CT scans acquired when lung cancer was first diagnosed in patients from six different institutions. What's more, the algorithm made its determination based not only on the size of the lesion but also on lesion texture and volume.

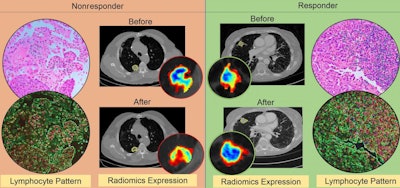

CT radiomic patterns showing higher density of tumor infiltrating lymphocytes on diagnostic biopsies after initiation of checkpoint inhibitor therapy (responder, right), compared with before (nonresponder, left). Image courtesy of Case Western Reserve University.

CT radiomic patterns showing higher density of tumor infiltrating lymphocytes on diagnostic biopsies after initiation of checkpoint inhibitor therapy (responder, right), compared with before (nonresponder, left). Image courtesy of Case Western Reserve University."This is important because when a doctor decides based on CT images alone whether a patient has responded to therapy, it is often based on the size of the lesion," co-author Mohammadhadi Khorrami said in a statement from the university. "We have found that textural change is a better predictor of whether the therapy is working."

Overall, the CT radiomics technique accurately predicted the response of patients to various immune checkpoint inhibitors with an area under the receiver operating characteristic curve of 0.88 in a testing cohort of 50 patients, 0.85 in a validation cohort of 62 patients, and 0.81 in another validation cohort of 27 patients.

When applied to a clinical setting, CT radiomics has the potential to reduce substantially the number of patients who undergo unsuccessful immunotherapy, which costs roughly $200,000 per year, Madabhushi noted.

"This is no flash in the pan -- this research really seems to be reflecting something about the very biology of the disease, about which is the more aggressive phenotype, and that's information oncologists do not currently have," he said.