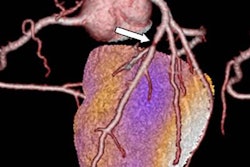

When coronary CT angiography (CCTA) images are viewed at a core laboratory, the chance of a stenosis being identified as significant is less than when readers at the local institution look at the same scans of patients with stable chest pain, researchers reported at RSNA 2017 last week.

In a study that involved nearly 5,000 patients, the core laboratory readers suggested that 13% of the CCTA scans revealed significant stenosis -- classified as obstruction of at least 50% -- compared with 23% of the scans reviewed at a local institution. Overall, that represented a 41% reduction in lesions being termed significant (p < 0.001), said Dr. Michael Lu, an assistant professor of radiology at Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School.

In addition, when catheter quantitative coronary artery stenosis of at least 50% was used as a reference standard, the core laboratory readers had an accuracy of 0.69 (area under the curve, AUC), compared with an accuracy of 0.57 AUC for readers at the sites (p < 0.001), Lu said in his presentation on November 27. The study was published online in the Radiology simultaneously with its presentation at the RSNA meeting.

Lu suggested that a more "parsimonious reading of the CCTA at the institutional sites would have resulted in a reduction of patients being sent for catheterization. However, there are conscious or unconscious biases that may push the reader to call more disease when trying to determine if a lesion is 45% or greater than 50%."

"These findings were robust across clinical reader expertise, the threshold for significant coronary artery disease, and the extent of coronary artery calcium," he said. "The core lab was more accurate with quantitative coronary angiography as the reference standard. Despite calling 41% less disease, the core lab had similar prognostic value for cardiovascular death and myocardial infarction."

The analysis was part of the Prospective Multicenter Imaging Study for Evaluation of Chest Pain (PROMISE), in which Lu and colleagues at 193 North American sites interpreted coronary CTA scans as part of the clinical evaluation of stable chest pain. CTA was also interpreted retrospectively by a central core lab blinded to clinical data, site interpretation, and outcomes.

The sites evaluated 4,347 patients, of whom 51.5% were women. Overall, the mean age of the participants in the study was 60.4 years.

Over a follow-up period of 25 months, 1.3% of the patients experienced a coronary event. There was a correlation of 0.67 for significant findings and an event in the core lab interpretations and a correlation of 0.68 for significant findings and an event in the local site interpretation of the scans (p = 0.71).

In commenting on the study, Dr. Jonathon Leipsic, vice chairman of radiology and an associate professor of cardiology and radiology at the University of British Columbia, suggested that the different environments under which the decisions were made as to whether the lesion in question was significant may have played a role in the discordant results.

"The drivers of the discordance may be that in the core lab we have a goal of greater accuracy, and the core lab readers are not biased by the symptoms of the patients," he noted, calling on his own experience as a core lab researcher. "The core lab reader is more risk-tolerant because we are not dealing with a patient but with a trial; we have no time constraints -- we have 48 hours to give an interpretation -- but that is very different than someone calling out from the ward asking about the patient they are clinically worried about; and we have an optimal reading environment with no interruptions."

On the other hand, "the physician reader is more focused on the patients; is biased by the patient symptoms; is risk-averse, especially with medical-legal concerns; and has constant interruptions," Leipsic said.

He said the PROMISE results leave him with several questions, for example: "Can we really expect core labs to make all our decisions, or are we going to accept overdiagnoses?"

Leipsic suggested that further testing of blood perfusion could help define which patients need to go to the cath lab. There is also the promise of artificial intelligence or deep-learning algorithms that may eventually play a role in the decision-making, he said.