Thyroiditis

Acute (Suppurative) Thyroiditis

Acute suppurative thyroiditis is a rare, and life threatening infection (abscess) of the thyroid gland [3]. It is most commonly a bacterial infection caused by Strep., Staph., or Pneumococcus. The diagnosis should be suspected in patients who present with fever, more localized tenderness warmth and erythema, and dysphoria or difficulty in swallowing. In 50-70% of cases, a preexisting thyroid disease is present. Most patients are clinically euthyroid (more focal thyroid involvement). The RAIU is usually decreased due to destruction of the gland. The infection can spread directly along the fascial planes of the neck or hematogenously producing a systemic sepsis. The local infection/inflammation in the neck can result in marked swelling which can compromise the airway, or cause vascular thrombosis in some of the major vessels.

Treatment is multifaceted and consists of surgical drainage, tracheostomy and antibiotics. In the rare patient who is clinically thyrotoxic, large doses of beta-blockers, saturated iodine solution or steroids may be beneficial. Thionamides are not indicated unless the patient has underlying Graves' disease.

Subacute Thyroiditis (de Quervain's Syndrome):

Pathophysiology

Subacute thyroiditis is characterized by lymphocytic, granulomatous, and foreign body giant cell infiltration. It probably has a viral etiology [3]. Pathologically, there is patchy involvement of the gland with mononuclear cell infiltrate and disruption of the normal follicular architecture. As the thyroid becomes damaged, hormone leaks out into the blood producing thyrotoxicosis. At this point, the thyroid gland has essentially stopped functioning because of the inflammation, and iodine uptake will be low. After hormone production resumes, the patient generally recovers without further complications.

Clinical Findings

Most patients are between 20-50 years of age. Females are affected more than men (5:1). Symptoms of subacute thyroiditis include the rapid onset of thyroid swelling and tenderness [3], which may mimic acute suppurative thyroiditis. Less severe complaints of a sore throat that radiates to the ears or angle of the jaw may also be seen.

Patients often have a preceding upper respiratory tract infection 2-3 weeks before. Patients may also experience a prodrome of fever, myalgias/aches, and fatigue [3]. The disease is usually self-limited, but patients may experience multiple episodes over a number of months. Patients typically recover fully without residual thyroid dysfunction (Only about 5% will be left with some degree of thyroid dysfunction. These individuals may have had underlying abnormalities prior to the acute episode)

Subacute thyroiditis progresses through a series of phases that dictate the clinical and scintigraphic findings. Initially there is a destructive phase with release of preformed thyroid hormone lasting 3-6 weeks [3]. Approximately 50% of patients present with symptoms of hyperthyroidism which lasts for 1 to 3 months. RAIU and TSH values will be low, while T4 and T3 levels will be moderately elevated. During this early period, ESR (>50) and WBC is often elevated. As hormone stores are depleted, patients return to a euthyroid state or go through a transient hypothyroid phase. At this point, patients may have decreased levels of T4, associated with increased TSH levels. With recovery, RAIU may be increased (>35%) due to a rebound phenomenon. There is usually a return to euthyroidism within 6-12 months [3]. Approximately 10% of patients require long term L-thyroxine therapy for treatment of persistent hypothyroidism [3].

Imaging

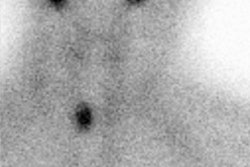

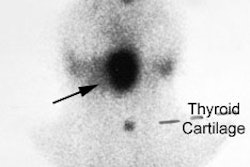

On scintigraphic examination of patients with early subacute thyroiditis there is typically poor visualization of the entire thyroid. Single or multiple hypofunctioning areas are occasionally seen as the disease can be focal and present as a cold area/nodule. Increased radioactive iodine uptake is seen during the hypothyroid phase (late) of the disease.

On ultrasound, there are patchy areas of hypoechogenicity which disappear as the clinical symptoms subside.

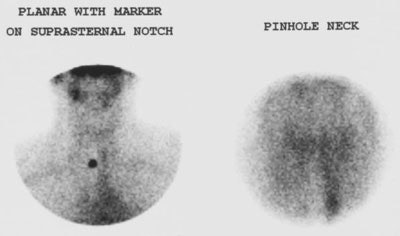

Subacute Thyroiditis: The patient presented with symptoms of hyperthyroidism. The T4 level was elevated and the scan was done to exclude Graves disease. The Tc-99m pertechnetate exam demonstrated no evidence of tracer accumulation in the neck consistent with subacute thyroiditis. Background blood pool and salivary activity can be seen. |

|

Treatment

Treatment of subacute thyroiditis includes salicylates (anti-inflammatory medications) and steroids if necessary to control the inflammation. Steroids produce a dramatic response, but are not recommended as there is recurrence of symptoms as the dose is tappered [3]. Beta-blockers may be used to control symptoms of thyrotoxicosis (tachycardia and tremor) [3]. Thionomides should not be used as the elevated T4 is due to the release of preformed thyroid hormones and not active synthesis. Patients who become hypothyroid and are symptomatic can be treated with thyroxine (T4). Thyroxine therapy can be discontinued after 6 months to 1 year to determine if there is recovery of endogenous thyroid function..

Silent (Painless/Thyrotoxic Lymphocytic) Thyroiditis:

Silent thyroiditis is an autoimmune disease that is characterized by elevated levels of thyroid peroxidase antibodies and thyroglobulin antibodies [1]. It is a form of lymphocytic thyroiditis with lymphocytic infiltration of the thyroid follicles that results in follicular cell damage and consequently, release of excess amounts of T4 and T3. The condition is differentiated from Graves' subacute thyroiditis in that patients experience no pain and there is no viral prodrome [3].

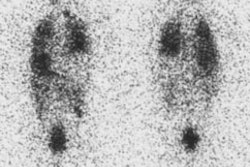

Patients typically have symptoms of thyrotoxicosis, but without a tender or painful thyroid associated with subacute thyroiditis (although the thyroid can be enlarged in 50-60% of affected patients [1]). T3 and T4 are elevated, the TSH is decreased, and the RAIU is decreased. ESR is normal and there is no history of preceding URI. The condition will generally resolve spontaneously [2]. The thyrotoxicosis is usually mild to moderate and lasts for 1 to 4 weeks (up to several months [2]), followed by a euthyroid period, and then transient hypothyroidism [1]. Most (80-90%) patients show complete recovery and return of the normal thyroid gland after 3 months [3]. Treatment with beta-blockers can palliate thyrotoxicosis symptoms and thyroid hormone therapy is sometimes needed during the recovery phase [1]. About 10% of patients will experience recurrent episodes of thyroiditis [2]. Recurrences can occur for about 4 years, but only a minority of patients develop persistent hypothyroidism. Thyroid scintigraphy reveals markedly decreased glandular activity [1].

Postpartum thyroiditis is seen in 5 % of post-partum patients. It is generally considered to be a subtype of silent thyroiditis that appears 2 to 12 months after delivery (most commonly between 4 to 6 months). The course and findings are similar to silent thyroiditis- thyrotoxicosis lasts 2 to 6 weeks and this is followed by a period of hypothyroidism which also lasts 2 to 6 weeks [1,2]. In contrast to the recovery of normal thyroid function that is expected in most patients with silent thyroiditis, between 20-33% of patients with postpartum thyroiditis will become permanently hypothyroid. The disorder tends to recur with multiple pregnancies [1].

Chronic Lymphocytic Thyroiditis: Hashimoto's

Pathophysiology

Hashimoto's thyroiditis is also known as chronic autoimmune thyroitditis [1]. It is an autoimmune disorder characterized by goiter and lymphocytic infiltration [1]. There is a familial predisposition. The autoimmune reaction associated with Hashimoto's consists of both cellular and humoral components. Auto-antibodies are a feature of the disorder. Antimicrosomal (anti-thyroid peroxidase [TPO] antibodies) are the most commonly found- 90-95% of patients [1] and are markedly elevated during the acute phase of the disorder. Unfortunately, anti-TPO antibodies are not specific for Hashimoto's as they are also found in 70% of patients with Graves disease. Antithyroglobulin antibodies (ATA) are found in 55-90% [1] of patients, most commonly and IgG antibody. Precipitin antibodies can also be identified and are very specific for Hashimoto's, but usually identified only late in the disease course.

Early on, there is mild, diffuse lymphocytic infiltration of the thyroid. As the disorder progresses there will be formation of germinal centers by the lymphocytes which replaces normal thyroid tissue. Late in the disorder there are plasma cell infiltrates, fibrosis, and destruction of the gland.

Clinical Findings

Hashimoto's is the most common inflammatory thyroid disease (accounting for about 85% of cases of thyroiditis). It is the most frequent cause of goiterous hypothyroidism in adults [4]. Females are affected more than males (9-15:1). Generally, patients are between the ages of 30-50 years [4], but the disorder may be seen at any age. Patients with Hashimoto's thyroiditis develop other autoimmune disorders with higher frequency and are at increased risk for developing B-cell lymphoma of the thyroid.

Initially, the gland enlarges due to a combination of the lymphocytic infiltrate, as well as hyperplasia and hypertrophy in response to elevated TSH levels. TSH is increased in these patients in response to falling thyroxine levels due to thyroid destruction. As a result of TSH stimulation of the remaining thyroid tissue, hormone levels tend to be maintained until late in the disorder, at the expense of an enlarged gland. Nodules may also form due to focal hyperplasia associated with long term TSH stimulation and intervening areas of fibrosis. Much less commonly, Hashimoto's can present as a focal nodule (focal lymphocytic thyroiditis or pseudotumor) [4].

Clinically patients present with gradual painless thyroid enlargement (firm rubbery gland). Patients may also complain of tiredness or a vague pressure in the neck. Uncommonly, patients may have a rapidly enlarging goiter and myxedema. Most patients are euthyroid at the time of presentation. TSH is typically normal, but will become elevated as patients become hypothyroid. TSH secretion stimulates the gland to synthesize more T3 and T4 so that levels stay normal. RAIU is typically normal until late in the disease course, but may be elevated in patients with Hashitoxicosis. ESR is normal. TRH test is also usually normal. Patients will demonstrate autoantibodies to thyroglobulin and thyroid peroxidase [4]. Unfortunately, antibodies can be absent in 13% of affected individuals and can also be found in 2-20% of the population without thyroid disease [4].

Eventually, as thyroid tissue is replaced by fibrosis, serum hormone levels will fall and patients become hypothyroid. About 20% of patients are hypothyroid at presentation (20%). Pain is rare, but if present, may mimic subacute thyroiditis (SAT). The RAIU will aid in differentiating the two conditions as RAIU is generally normal in Hashimoto's, but is decreased in SAT. Thyrotoxicosis is also rare (4%) and may be related to the release of thyroid hormone during the early stages of the disorder.

Hashitoxicosis: Hashimoto's thyroiditis can also manifest as an acute mild to moderate hyperthyroidism in 3-5% of cases. Hashitoxicosis refers to the presence of chronic lymphocytic thyroiditis PLUS hyperthyroidism. These patients have high antibody titers as seen in Grave's disease (in fact, this disorder probably represents superimposed Grave's on Hashimoto's). The antigen-antibody reaction leads to relatively rapid follicular cell damage and excess hormone release into the circulation [1]. RAIU is normal or elevated. The hyperthyroidism is typically self-limited and resolves spontaneously over a period of weeks to several months [1].

Juvenile Hashimoto's is characterized by remissions and recurrences, and is treated with T4 therapy.

Complications of Hashimoto's include: Hypothyroidism, an increased risk for thyroid lymphoma, and an increased risk for Grave's Disease and other autoimmune disorders such as pernicious anemia, etc...

Imaging

The scintigraphic appearance of Hashimoto's is variable. A multinodular goiter appearance is common with multiple (40%) or single (30%) cold defects. There can be diffuse, uniform increased tracer activity, to a coarse patchy distribution of tracer, or focal/diffuse absence of activity. The pyramidal lobe may appear prominent due to TSH stimulation. A normal scan is seen in about 8% of patients. Until thyroid reserve is disrupted, patients typically have a normal RAIU.

On ultrasound, the gland is generally diffusely enlarged with a loss of the normal homogeneous echo texture of the thyroid. The gland is typically hypoechoic, inhomogeneous, hypervascular and discrete nodules may be noted occasionally. Another feature that has been reported to be highly diagnostic of Hashimoto's (PPV 95%) is the presence of hypoechoic 1-7mm micronodules [4]. Later, fibrosis results in increased echogenicity (coarsened echotexture).

Treatment

Patients are treated with thyroxine (T4). This helps to prevent further thyroid enlargement and decreases the formation of nodules by suppressing TSH. Thyroid hormone replacement is also indicated in patients who are hypothyroid (low T4, elevated TSH) or with subclinical hypothyroidism (normal T4, elevated TSH) who are at risk of progressing to overt hypothyroidism. Thyroxine therapy does not affect the lymphocytic infiltrate or decrease the risk for subsequent thyroid lymphoma.

Riedel's Thyroiditis: (Riedel's Struma)

Riedel's struma is a rare condition that has also been referred to as invasive fibrous thyroiditis. In this disorder, there is painless replacement of the thyroid by dense fibrous tissue and which may also involve adjacent soft tissues of the neck and is often mistaken for cancer. Between 30 to 40% of patients will progress to hypothyroidism as the infiltrative progress involves the gland.

REFERENCES:

(1) Radiographics 2001; Intenzo CM, et al. Scintigraphic features of autoimmune thyroiditis. 21: 957-964

(2) Radiographics 2003; Intenzo CM, et al. Scintigraphic manifestations of thyrotoxicosis. 23: 857-869

(3) J Nucl Med 2008; Mittra ES, et al. Uncommon causes of thyrotoxicosis. 49: 265-278

(4) AJR 2010; Anderson L, et al. Hashimoto thyroiditis: part I, sonographic analysis of the nodular form of Hashimoto thyroiditis. 195: 208-215