Using a surface-based MRI method to measure cortical thickness, Italian researchers have found that migraine headaches may be related to brain abnormalities present at birth and other abnormalities that develop over time, according to a study published online in Radiology.

The study's findings could be among the first steps to better confirming prognosis and developing effective treatment for the more than 30 million people estimated by the World Health Organization to suffer from migraine headaches.

Intense migraines can be accompanied by nausea, vomiting, and sensitivity to light. Some patients also experience auras, which are a change in visual or sensory function that precedes the migraine or occurs during it. Previous research on migraine patients has shown atrophy of cortical regions in the brain related to pain processing, possibly due to chronic stimulation of those areas.

"Migraine is a frequent and troublesome condition, which is still poorly understood," wrote study co-author Dr. Massimo Filippi, director of the Neuroimaging Research Unit at University Ospedale San Raffaele and professor of neurology at Vita-Salute San Raffaele University's Scientific Institute in Milan, in an email to AuntMinnie.com. "For a long time, it is known that a proportion of migraine patients harbor white-matter lesions of possible vascular origin and, more recently, that they also have cortical abnormalities."

Brain abnormalities

Several years ago, lead study author Dr. Roberta Messina, Filippi, and colleagues began to study these patients using MRI to define the structural and functional abnormalities associated with migraines. Their goal was to identify factors leading to this condition and to offer markers to monitor its evolution and the effects of treatment.

Between January 2009 and December 2011, the researchers prospectively examined 63 patients with migraines, along with 18 healthy control subjects. The study's inclusion criteria included no previous history of neurologic dysfunction; normal findings at the time of neurologic examination; no special talents such as athletic or musical abilities; no vascular and/or heart disease; and no other major systemic, neurologic, or psychiatric conditions (Radiology, March 26, 2013).

At the time of their MRI scans, 19 (30%) of the 63 participants with migraines were receiving medication for the condition, according to the authors.

Patients were imaged on a 3-tesla MRI scanner (Intera, Philips Healthcare) with the following sequences: T2-weighted turbo spin-echo imaging; fluid-attenuated inversion recovery imaging; and 0.9-mm-voxel isotropic 3D T1-weighted fast-field-echo imaging. Cortical reconstruction and estimation of cortical thickness and cortical surface area were done on the 3D T1-weighted fast-field-echo images.

After estimating cortical thickness and surface area, the researchers correlated it with the patients' clinical and radiologic characteristics.

Messina and colleagues compared the healthy control subjects and patients with migraines; patients with aura and patients without aura, separately, with the healthy control subjects; and patients with and those without white-matter hyperintensities (WMH), separately, versus the healthy control subjects.

Migraine frequency

Patients with migraine and no aura had a greater frequency of migraine attacks and attacks of a longer duration compared to migraine patients with aura, the researchers found.

Comparisons between the subgroups showed some differences and similarities among the study cohort. Patients with migraines exhibited an increased average cortical thickness (mean, 2.08 mm ± 0.07) compared to control subjects (mean, 2.02 mm ± 0.07). However, the average cortical surface area did not differ between patients with migraine (mean, 866.12 cm2 ± 88.6) and control subjects (mean, 863.58 cm2 ± 72.4).

No white-matter lesions or hyperintensities were found in healthy control subjects or in 39 (62%) of the 63 patients with migraines. In addition, the average cortical thickness did not differ between patients with or without WMHs.

Among patients with migraines, the average cortical thickness and average cortical surface area did not differ between those with aura and those without aura. However, the average cortical surface area was significantly lower in patients with WMHs (mean, 834.8 cm2 ± 66.8) than in patients with no WMHs (mean, 885.3 cm2 ± 95.5).

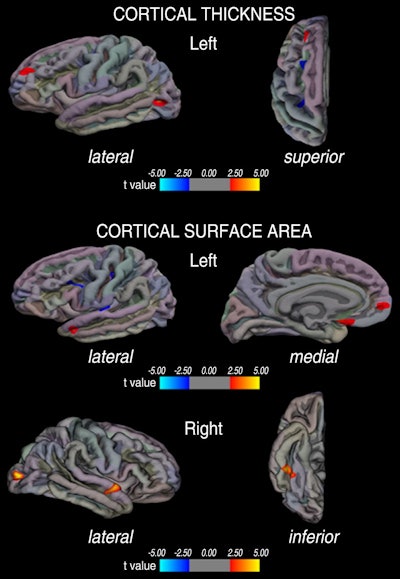

Image shows regional differences in cortical thickness and cortical surface area in patients with migraine compared with healthy control subjects. Regions of increased cortical thickness or surface area are shown in red and regions of decreased cortical thickness or surface area are shown in blue. Image courtesy of Radiology.

Image shows regional differences in cortical thickness and cortical surface area in patients with migraine compared with healthy control subjects. Regions of increased cortical thickness or surface area are shown in red and regions of decreased cortical thickness or surface area are shown in blue. Image courtesy of Radiology.In brief, Filippi and colleagues found that migraine patients do have reduced cortical surface area and cortical thickness of regions that are part of the pain-processing network, and these two types of abnormalities do not fully overlap.

Interestingly, the cortical surface area increases dramatically during late fetal development as a consequence of cortical folding, and cortical thickness changes dynamically throughout the entire life span as a consequence of development and disease, they added.

"Based on these findings," Filippi said, "the main take-home message of this study is that migraine patients might have a sort of cortical signature or abnormal cortical surface area, which could make them more susceptible to pain and abnormal processing of painful conditions and stimuli. Then, the occurrence of disease might lead to additional cortical abnormalities, such as reduced cortical thickness."

One issue still under debate is whether the abnormalities are a result of repeated migraine attacks or represent an anatomical condition that predisposes individuals to the development of the disease. These factors might make migraine patients more susceptible to pain and to an abnormal processing of painful conditions and stimuli, Filippi said.

Future research

Given this study's small patient cohort, Filippi and colleagues are now investigating larger numbers of patients to confirm these results and to explore the evolution of cortical abnormalities and their role in disease prognosis and treatment response.

"First, we are following up this patient cohort to understand whether these cortical abnormalities are stable or tend to worsen over time," Filippi said. "Second, we are conducting a similar study in pediatric migraine patients. These two projects should allow us to shed light on the meaning of the observed abnormalities. Are they the cause or the result of the pathological condition? Third, we are assessing the effect of drugs on such changes to assess their clinical value."

If the results confirm the clinical expression of the disease and that the condition worsens over time, it would have a "dramatic impact on managing these patients, especially to monitor the efficacy of treatment," Filippi said.