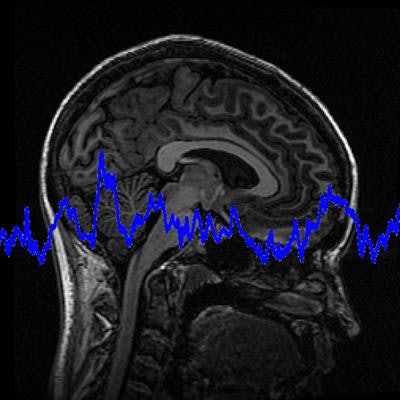

Ultrasound scans with a robotic transcranial Doppler device provided a clue into why patients with COVID-19 experience severe hypoxemia without lung stiffness. In a serendipitous discovery, researchers linked the ultrasound findings to suspiciously low oxygen levels in patients with severe cases of COVID-19.

The researchers used a robotic transcranial Doppler (TCD) ultrasound system to assess cerebral blood flow in 18 patients with severe COVID-19 pneumonia. They had been looking for stroke and other cranial abnormalities, but they instead found that the majority of patients had detectable microbubbles, a finding that indicates abnormally dilated pulmonary blood vessels.

"This study helps explain the strange phenomenon seen in some COVID-19 patients known as 'happy hypoxia,' where oxygen levels are very low, but the patients do not appear to be in respiratory distress," stated senior author Dr. Hooman Poor, an assistant professor at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in a press release. Poor and colleagues published their research on August 6 as a letter in the American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine.

In patients with classic acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), pulmonary inflammation results in blood vessel changes that make the lungs stiff and impair oxygenation. But the amount of hypoxemia seen in patients with COVID-19 is often drastically out of proportion with lung stiffness.

The new pilot study revealed that vasodilation could help explain why COVID-19 pneumonia differs from classic ARDS. Using transcranial Doppler ultrasound scans, the researchers found that 83% of patients had detectable microbubbles. In addition, the number of microbubbles correlated with hypoxemia severity in patients with severe COVID-19.

In comparison, only about 26% of patients with classic ARDS show detectable microbubbles on transcranial Doppler scans. The number of microbubbles also did not correlate with hypoxemia severity for patients with classic ARDS.

"It is becoming more evident that the virus wreaks havoc on the pulmonary vasculature in a variety of ways," stated Poor.

The study included 18 patients with severe COVID-19 pneumonia who also had altered mental status and required mechanical ventilation. The patients underwent robotic transcranial Doppler ultrasound (Lucid Robotic System by NovaSignal) with an agitated saline solution.

The researchers injected the contrast agent in an upper extremity or through a central line in the internal jugular vein. NovaSignal's ultrasound software automatically counted the number of microbubbles detected over 20 seconds, and the researchers manually counted and confirmed the number of microbubbles as a precaution.

In healthy patients, the contrast microbubbles enter the lung blood vessels and get filtered out by pulmonary capillaries. If bubbles are detected in the brain, it indicates that the patient either has a hole in the heart or that the capillaries are abnormally dilated, which the researchers believe might be contributing to hypoxemia in patients with COVID-19.

Poor and his team at Mount Sinai are continuing their research and have thus far collected data from roughly 80 patients with various COVID-19 severity. The team plans to analyze microbubble transit, including how transit varies throughout the course of the disease.

"If these findings are confirmed in larger studies, pulmonary microbubble transit may potentially serve as a marker of disease severity or even a surrogate endpoint in therapeutic trials for COVID-19 pneumonia," Poor stated. "Future studies that investigate the use of pulmonary vascular constrictors in this patient population may be warranted."