AuntMinnie.com presents the 18th in a series of columns on the practice of ultrasound from Dr. Jason Birnholz, one of the pioneers of the modality.

Consider this: Wherever a physician encounters a patient is his or her "point of care." The traditional diagnostic tools -- the history and physical -- are portable and can be used with a variety of devices either in emergency situations in the field or at the bedside in a medical center with all kinds of available resources.

Dr. Jason Birnholz.

Dr. Jason Birnholz.I was more than fortunate to have the use of one of the two first commercially available phased-array ultrasound systems at the start of 1976 when I was at Stanford University. The other unit went to Dr. Richard Popp in the cardiology department. It was big and bulky -- weighing a few hundred pounds -- but it had pretty good-sized wheels and could be moved around by one person. That was my main form of exercise for a while.

While it had excellent performance, the unit was limited to a 2.25-MHz transducer, so the applications were for deep organs in large children and adults. Initially, I trudged it over to individual patients who were immobile in intensive care units (ICUs) and critical care units (CCUs). Later, I trekked to places with a collection of patients in facilities where there was no ultrasound yet, such as the Children's Hospital located across the campus.

Population-screening ultrasonography

When I returned to Boston in September of 1976, I obtained two phased-array units for my ultrasound facilities at the Boston Hospital for Women and at the Peter Bent Brigham Hospital; those two institutions merged into a combined, new facility about five years later. The space designated for the ultrasound unit at the Brigham was so small that I had an extra incentive to move the unit around.

One place was the coronary care unit, where I worked with Dr. Josh Wynne on what might well have been the first use of high-speed ultrasound imaging to look at regional wall movement abnormalities with suspected and established myocardial infarctions. I've mentioned this before.

However, at the other end of the care spectrum was something more similar to a mass screening trial conducted in the radiology department. In the midst of inpatients on the way to procedures in wheelchairs and on stretchers, a line of volunteers walked past a privacy partition to the ultrasound machine, raised their shirts or blouses, and received a gallbladder look. None had been asked to fast.

The summary, titled "Population Survey: Ultrasonic Cholecystography," appeared in Gastrointestinal Radiology in 1982 (Vol. 7:1, pp. 165-167). There were some 766 subjects with an average scan time of 30 seconds. Adequate visualization occurred in over 98%. The end point was cholelithiasis, which was found in 33% of people with right upper-quadrant complaints and in 11% of asymptomatic individuals.

The incidences of cholelithiasis in that study are not the issue, since that factor is a characteristic of the study population. However, it was a pretty good demonstration of how powerful ultrasound can be in a designated screening role, especially considering the limitation of a first-generation, phased-array device with a single 2.25-MHz probe 30 years ago.

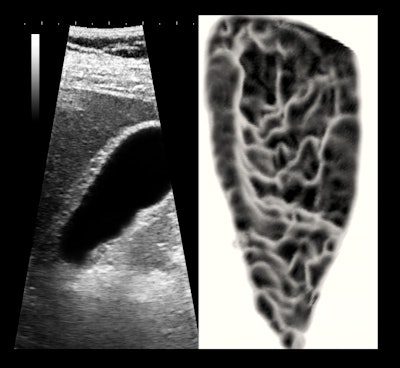

If I were to do something similar today and be limited to a midperformance unit, I would add inspection of the anterior wall for chronic focal cholecystitis, since this finding seems to precede stone formation by several years. I would also rely on 3D surface rendering of the lumen, because even a half-second scanning of 16 frames will improve the signal-to-noise ratio by 400% over a single-frame image (see below).

Patient with severe chronic focal cholecystitis. Left: 5-MHz narrow-sector, high-persistence image. Right: cutaway, magnified, reversed-phase 3D surface rendering showing the sinuous fibrotic scarring of the anterior lumen. All images courtesy of Dr. Jason Birnholz.

Patient with severe chronic focal cholecystitis. Left: 5-MHz narrow-sector, high-persistence image. Right: cutaway, magnified, reversed-phase 3D surface rendering showing the sinuous fibrotic scarring of the anterior lumen. All images courtesy of Dr. Jason Birnholz.At about the time of that gallbladder screening protostudy, Dr. Martin Carey, also at Brigham and Women's Hospital, had shown that gallstone formation might be prevented by daily low-dose aspirin (Science, March 27, 1981, Vol. 211:4489, pp. 1429-1431).

The flip side of mobile ultrasound

Moving equipment is a way of providing a diagnostic resource where it is not immediately available. In a private-office setting -- or an ambulatory outpatient ultrasound facility, to be classier -- equipment is fixed in a location, but the other ancillary resources of a hospital or large multispecialty clinic are absent.

In my hospital years, no one was seen in my units unless their chart was there, excepting emergency exams, of course. My main problem in my solo office was a lack of detailed information about patients referred for a study.

That is not to say that my referring physicians did not express their concerns about their patients to me, but I only occasionally had actual lab values or reports of other imaging studies, operative reports, biopsy results, or records from past medical interactions. Hopefully, the uniform electronic medical record platforms will lift that diagnostic impediment for nonhospital-associated offices. What I did was use desktop ancillary medical devices to provide information that I could not get from ultrasound or my old black-bag physical exam tools.

A fundamental lesson from bone density

Bone density from a self-contained phalangeal x-ray unit was one such device. I was impressed with the works of my classmate and fellow internal medicine intern Dr. Richard Wasnich on the relationship between bone density and breast cancer risk. Using demographic information and a very good technique for bone density, he had developed an algorithm for estimating a lifetime breast cancer risk.

He had realized that bone density in women is related to cumulative estrogen levels similar to the way hemoglobin A1C (glycosylated hemoglobin) is used now in diabetes detection instead of a spot measurement of glucose level. There were also some interesting works on bone density and endometriosis and on fetal growth versus maternal bone density in the first trimester of pregnancy back then in the 1990s. I incorporated this form of bone density as a free, voluntary add-on for our referred female patients.

To digress from the clinical issues, I think the notion of value-added, no-charge diagnostic testing is an important concept for an ultrasound facility involved in high-level diagnostic work. On the economic side, when third-party payors don't pay for services as billed appropriately or delay payment significantly through any of a number of familiar ruses, then the typical response of the practice is to raise prices, if they can, or narrow the focus of the exam, if they cannot.

Manufacturers of ancillary diagnostic equipment tend to market the reimbursable nature of their products as equal to or more important than their potential clinical value. Practices of all kinds adopt them for both clinical value and as an additional revenue stream, which third-party payors question, ratcheting up the process over and over again.

This is even more problematic if the add-on is redundant. Third-party payors need to reimburse reasonably, and we need to utilize whatever each practice or facility requires to meet their diagnostic obligations as well as they can without a separate billing for every possible addition to a study. Progressive underreimbursement provokes a clinical death spiral.

The century-old relationship between breast cancer and estrogen has been a major research concern, i.e., the excellent review in the New England Journal of Medicine by James Yager, PhD, and Dr. Nancy Davidson (January 19, 2006, Vol. 19:354, pp. 270-282). We know that breast tissue concentrates estrogen, and several of the pathways of estrogen metabolism have been unraveled.

You can determine a risk of breast cancer from bone density. However, that estimate ignores individual differences in breasts even in ethnic- or age-stratified cohorts. An estimate of cumulative estrogen and a measurement of parenchymal volume of the breast together make a lot more sense.

Something that every radiologist knows is that there is no one imaging test that provides a full picture of any organ. An integral part of radiology is to understand what each imaging method shows, what it doesn't, and how to select the best starting point for an evaluation given whatever is known clinically about the patient at the time of contact.

Even though we may practice ultrasound in clinical isolation, we should never disregard the fundamental necessity for seeking a diagnosis or path to a diagnosis through a synthesis of complementary sources of information.

AdvaMed 2014

I was really excited to be asked to attend this year's conference of the Advanced Medical Technology Association (AdvaMed), because this is a meeting where brand-new diagnostic devices are introduced. AdvaMed claims to be the "world's largest medical technology association representing manufacturers of medical devices, diagnostics products, and medical information systems."

I attended AdvaMed 2014 primarily as a journalist. There were some bright spots that just stunned me, but before I get to them, I want to express my thanks to the people of Brightline Strategies who managed all of the media people attending the meeting. Overall, the meeting was mainly about the business of medical devices, such as how to safely navigate regulatory waters. A lot of the manufacturers made comments about helping patients, but there seemed to be little attention to the physicians or medical personnel who would be using those devices in delivering care.

Medical imaging was not well-represented, but there were some novel ways of physiologic sensing with ultrasound. I was blown away by the elegance of a new concept: a diffraction grating ultrasound transducer. It's a thin piezoelectric grid within a bioinert membrane, smaller than a postage stamp, and very efficient as a transducer, requiring very, very little power. The beam is shaped and directed by interference patterns at the surface of the interdigitated grating electrodes.

I interviewed John M. Turner, PhD, president and CEO of Arterium Medical, who said that the company's inexpensive, disposable transducer has been developed and optimized for Doppler evaluation of superficial arteries. What astounded me was that the operating frequency is 40 MHz. That's at least 10 times higher than even the best that we are used to. This is so important because the backscatter from blood is proportional to the fourth power of frequency. This is the Tyndall effect.

The consequence is that the Doppler signal is extraordinarily clean and that all kinds of hemodynamic information can be extracted from the signal that's lost in noise in the conventional frequency range. The primarily clinical applications may be in critical care and intraoperative situations. In the back of my mind, I was thinking about surface and endocavitary probes, neovascularity, and malignant tumor detection. All of which is to say: something new with a really fantastic clinical potential.

The second surprise was Direct Relief, a U.S.-based, international nonprofit organization. I spoke with Ashley Cooley from their home office in Santa Barbara, CA, and learned that they support medical clinics in about 80 countries, as well as all 50 of our states. They have been around for more than 60 years and have a core mission of increasing access to medications in underserved and indigent populations.

An important part of their current activities is a maternal- and child-health program. They distribute medical supplies and provide educational support for local resources. They were at this meeting because they also distribute medical devices.

For the most part these are uncomplicated, rugged basic-care units. However, they have been investigating how best to integrate ultrasound into their pregnancy-care initiatives, particularly in field triage, where a clinic and some level of professional care may be two or three days' walk away. This seemed to me to be a great example of sharing the best of the expertise we have acquired broadly and ideally by need and availability.

Madam Secretary

Hilary Rodham Clinton gave the keynote address at AdvaMed 2014. I was rapt right at the start when she cited handheld ultrasound as already making a major contribution to women's health in the developing world. She talked about improving what we have in "sensible ways." She cited her experience with the Arkansas Rural Health Program and detailed ways that affordable healthcare enhances innovation and seeks to improve the quality and availability of care.

Former Secretary of State Hilary Rodham Clinton speaking at AdvaMed 2014.

Former Secretary of State Hilary Rodham Clinton speaking at AdvaMed 2014.She implored medical device manufacturers to share U.S. ingenuity by placing those tools in the hands of physicians and healthcare workers globally, and suggested that this was in the spirit and part of "our most important export, our values." Most compelling for me as a physician was her assertion that it is our obligation to provide healthcare for the needy. Practicing physicians know this, but not everyone providing support for physicians and nurses has made this a core value.

During my academic days, I did a lot of lecturing, and I had the good fortune and privilege of meeting ultrasound people pretty much everywhere. I always learned a lot, especially from places that didn't see themselves as expert or in possession of all the answers. Over and over again, I saw ultrasound done with the best of intentions, with sympathy and understanding for our patients, and with whatever resources were at hand.

This is the heartwarming spirit implicit in Mrs. Clinton's address. Where we work are our points of caring, be they fixed or mobile and with whatever tools we conscript to help us.

Dr. Jason Birnholz was one of the few advanced academic fellows of the James Picker Foundation, and he has been a professor of radiology and obstetrics. He is a fellow of the American College of Radiology and the Royal College of Radiology, and he was an associate fellow of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

The comments and observations expressed herein do not necessarily reflect the opinions of AuntMinnie.com.