MRI scans show that young athletes with a history of concussion sustain more brain injury from later concussive events compared with those players with no such history, according to a study published August 25 in Neurology.

The findings shed light on the far-reaching effects of concussion, according to study senior author Tom Schweizer, PhD, of St. Michael's Hospital in Toronto.

"We know concussions may have long-term effects on the brain that last beyond getting a doctor's clearance to return to play," he said in a statement released by the journal. "It is unclear, however, to what extent the effects of repeated concussion can be detected among young, otherwise healthy adults. We found even though there was no difference in symptoms or the amount of recovery time, athletes with a history of concussion showed subtle and chronic changes in their brains."

Schweizer and colleagues conducted a study that included 228 athletes (average age, 20) who played football, volleyball, and soccer. Of these, 61 had sustained a recent concussion and 167 had not. Among the 61 who had recently concussed, 36 had a history of concussion; among the 167 who had not sustained a recent concussion, 73 had a history of it. Recently concussed participants received up to five brain MRI exams that spanned time of injury to one year after returning to play.

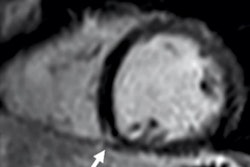

The group focused on MRI findings regarding decreases in blood flow to the cingulate cortex, which coordinates sensory and motor skills, as well as changes to the white-matter microstructure in the corpus callosum. Both of these characteristics can point to injury to the brain.

The group found that among athletes with a history of concussion, at one year after the most recent event they showed decreased blood flow in the cingulate cortex.

| Cerebral blood flow on MRI among athletes without and with history of concussion | ||

| Measure | Athletes without history of concussion | Athletes with history of concussion |

| Cerebral blood flow (per 100 g of brain tissue) | 53 mL per minute | 40 mL per minute |

The researchers also found that those athletes with a history of concussion showed more microstructural changes to the part of the corpus callosum called the splenium compared with athletes without concussion history in the weeks after a new injury.

"Our findings suggest that an athlete with a history of concussion should be watched closely, as these subtle brain changes may be worsened by repeated injury," Schweizer said. "Additionally, our results should raise concern about the cumulative effects of repeated head injuries later in life."

Study disclosures

The study was supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, the Canadian Institute for Military and Veterans Health Research, and Siemens Healthineers Canada.