While some people might wish to forget the experience of undergoing an MRI exam, others turn it into art. Inspired by scans of her own brain, California artist Laura Jacobson recently created a permanent collection of works for the Stanford Center for Cognitive and Neurobiological Imaging (CNI).

Ceramic sculptures, etchings, and acrylic paintings, all reflecting various aspects of brain imaging, were shown in June in the center, which opened approximately two years ago. Jacobson was approached about the project after neuroscientists saw her work based on her own MR images acquired during testing of a 3-tesla scanner.

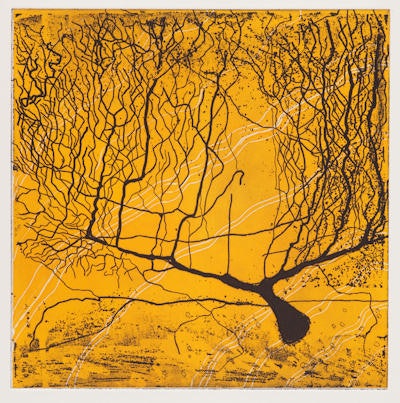

Neuron No. 3 etching. All images courtesy of Laura Jacobson.

Neuron No. 3 etching. All images courtesy of Laura Jacobson."The director of the CNI, Brian Wandell, approached me to make artwork for the center shortly after he and several colleagues (independently) visited my studio," she told AuntMinnie.com by email. "I had volunteered as a research subject to test the new 3-tesla magnet a few months before and had been using the scans I received then to make clay wall sculptures based on my axial slices."

The work "Resonance Punctuated," which consists of 10 colorful clay sculptures, hangs in the lobby of the CNI. Jacobson used her own MRI scans as the reference for creating the general brain anatomy, and she also added different textures to the works, pressing everyday industrial materials such as circuit boards and auto parts into the clay. The result is a mix of the old and the new, using elements of Silicon Valley and other technology to create a "contemporary artifact or an urban fossil."

The hope is that the sculptures will provide a tactile, more welcoming atmosphere for subjects coming into the research setting, she noted.

Resonance Punctuated. Detail is shown below.

Resonance Punctuated. Detail is shown below.

Creating the collection offered a "unique opportunity to use cutting-edge technology of MRI to peer into the mind and find inspiration in the patterns and structures of cerebral anatomy," she said. "Combining this with one of the oldest technologies -- ceramics -- is perhaps what makes the project in the lobby so fresh. The prints and the paintings ... also use traditional media to describe biological landscapes only recently visualized through new technologies."

The two etchings, "Neuron No. 3" and "Position," are located down the hall, Jacobson said. "Neuron No. 3" aims to convey the beauty of neuronal structure while reflecting the history of neuroscience. It draws upon the 1837 discovery of Purkinje cells, a type of large neuron, by Jan Evangelista Purkinje; the staining method developed by Camillo Golgi that illuminated the structure of nervous tissue; and Santiago Ramón y Cajal's drawings of nerve cells.

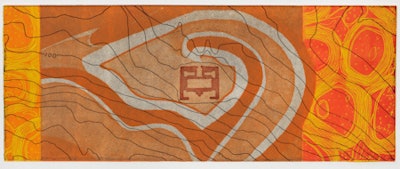

"Position" once again takes a more local turn, combining maps of Stanford's campus and the quadrangle in which the CNI is located with a cross-section of the hippocampus, which is involved in memory and spatial navigation. The etching "engages with the idea of mapping as it relates to the hippocampus and to the broader goal of functional brain imaging," according to Jacobson.

Position.

Position.The final piece consists of acrylic paintings and is titled "Acquisition." The two-panel work "refers to data collection and the acquisition of knowledge and celebrates the use of MRI for scientific inquiry," Jacobson said. Those familiar with imaging will recognize the bed and bore of an MRI scanner, which also resembles an eye looking toward the observer. The paintings also incorporate the movement of red blood cells, the chemical structure of hemoglobin, and MRI pulse sequences.

Acquisition.

Acquisition.Jacobson's previous work has investigated the biological form, but the link with medical imaging is a newer development. "The work has been percolating for several years as my life partner is a neuroscientist who used me as a guinea pig in the MRI (many, many times) while he was still a graduate student 20 years ago," she said.

The goal of the CNI is to support projects that connect neuroscience and society, advancing discovery and research and disseminating new imaging methods. Research participants and others coming to the center are interested in science and the brain, and CNI wanted a space where they felt comfortable and could learn about neuroscience, said center director Wandell.

"We knew [Jacobson's] art and felt that she has a very good feel for both the science and how the science feels to us and the subjects," he told AuntMinnie.com. "We commissioned these pieces because we felt they would help us with our mission of working with and for people."