German researchers have found promising evidence that PET/MRI is equivalent to PET/CT for lesion detection in pediatric cancer patients, while at the same time delivering just one-quarter of the radiation dose, according to a study published in the October issue of Radiology.

Separately, MRI provided substantial additional clinical information, especially in soft-tissue lesions that were deemed negative with PET.

"Taken together, our results suggest that PET/MR imaging is a promising modality for pediatric oncology with intrinsically lower radiation exposure than PET/CT and should be considered for juvenile patients wherever available," wrote lead author Dr. Jürgen Schäfer from Eberhard Karls University Tübingen in Germany (Radiology, October 2014, Vol. 273:1, pp. 220-231).

A good match for kids

On the surface, PET/MRI would appear to be a good match for pediatric patients. While FDG-PET/CT can be used to stage and evaluate solid tumors in children, MRI has performed well for certain pediatric malignancies, including lymphomas and sarcomas, without exposing patients to the radiation that is emitted by CT.

As Schäfer and colleagues noted, previous studies have shown that PET/MRI provides equivalent results to PET/CT in adults with cancer (Journal of Nuclear Medicine, June 2012, Vol. 53:6, pp. 845-855). However, no comparable studies have been done to gauge PET/MRI's efficacy in children.

"Compared with adults, children and juveniles display substantially different physiological characteristics, such as age-dependent specific fat and bone marrow distribution and bone density," Schäfer and colleagues wrote.

The current study included nine boys (mean age, 14.1 years ± 2.1) and nine girls (mean age, 14.3 years ± 2.8). PET/CT and PET/MRI scans were performed sequentially on the same day for each patient. A total of 20 exams were done on the 18 patients.

PET/CT scans were performed with a state-of-the-art scanner (Biograph mCT, Siemens Healthcare) with intravenous injection of 228 MBq (± 69 MBq) of FDG based on body weight. Simultaneous PET/MRI was conducted on a whole-body system (Biograph mMR, Siemens) with a 3-tesla MRI scanner and PET system with lutetium oxyorthosilicate (LSO) detectors.

The researchers measured PET standardized uptake values (SUVs) for lesions and healthy tissues, and lesion detection was assessed with separate reading of PET/CT and PET/MRI results. In addition, they estimated radiation dose from the applied doses of FDG and CT protocol parameters.

Lesion detection

PET/MRI and PET/CT achieved similar lesion detection rates, the researchers found. There were 62 areas of focal FDG uptake on PET/CT images in 12 of the 20 scans. PET/MRI detected 61 (98%) of those areas, the lone exception being one lung lesion with focal uptake that was discovered only on PET/CT.

In addition, PET SUVs were similar regardless of the modality with which it was paired. However, there was a small decrease in SUV (-10.1%) in bone marrow when PET/CT was performed first and an increase in SUV (+20.1%) when PET/CT was done after PET/MRI.

The anomaly was due to bone being "neglected" in MRI attenuation correction using a Dixon-based method, which can result in an "underestimation of attenuation and consequent overestimation of SUVs in tissues adjacent to osseous structures," such as bone marrow, in PET/MRI, Schäfer and colleagues wrote.

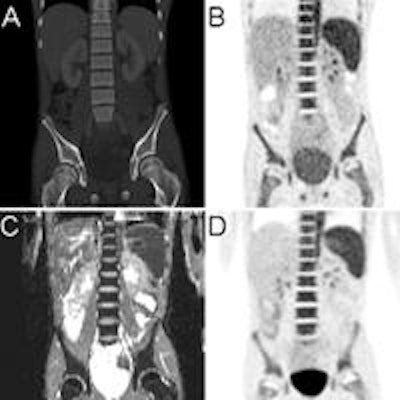

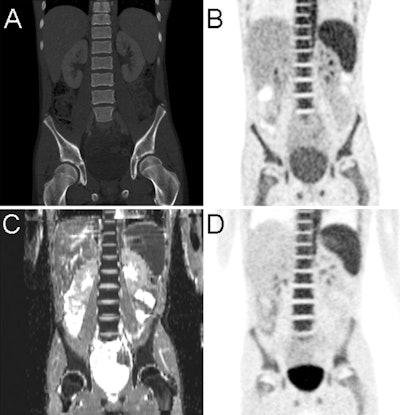

Images are of a 14-year-old patient with non-Hodgkin's lymphoma and bone marrow infiltration. PET from PET/CT (B) and PET from PET/MRI (D) show increased bone marrow uptake, paralleled by diffusion restriction shown on the apparent diffusion coefficient map (C). CT (A) findings of the PET/CT examination were inconclusive. Images courtesy of Radiology.

Images are of a 14-year-old patient with non-Hodgkin's lymphoma and bone marrow infiltration. PET from PET/CT (B) and PET from PET/MRI (D) show increased bone marrow uptake, paralleled by diffusion restriction shown on the apparent diffusion coefficient map (C). CT (A) findings of the PET/CT examination were inconclusive. Images courtesy of Radiology.As expected, MRI's higher soft-tissue contrast was able to identify diagnostic information in lesions that were interpreted as negative with PET.

"Thus, relevant additional findings were detected in four patients at PET/MR imaging compared with PET/CT," the authors wrote.

Conversely, CT discovered multiple lung metastases in two patients with sarcoma, which were only partly visible with MRI. PET/MRI also upstaged two pediatric cancer patients and found recurrence in two other children, resulting in a possible change in patient management.

Radiation exposure

The study also showed that PET/MRI delivered much less radiation to patients than PET/CT, as measured by mean size-specific dose estimate (SSDE).

The mean effective dose of whole-body PET/CT was 23 mSv (± 11 mSv), with PET accounting for 5.6 mSv (± 1.5 mSv) and CT accounting for 18.2 mSv (± 10 mSv). Thus, CT accounted for 73% (± 11%) of the total effective dose -- dose not present in the PET/MRI scans.

Consequently, the authors concluded, a "marked reduction of about 73% in radiation dose can be achieved by using PET/MR imaging compared with PET/CT."

"In this initial study, we have shown that PET/MR imaging results are comparable to those of PET/CT in identifying lesions with increased FDG uptake in pediatric patients with solid tumors," Schäfer and colleagues wrote. "As expected, additional diagnostic information was obtained with MR imaging data in areas of soft tissue."

The authors cited several limitations of the study, including a "relatively inhomogeneous patient population. This limits our ability to assess the relative value of PET/MR imaging in specific tumor entities or for specific indications," they wrote.

They also noted a case selection bias, in that they only included patients who were able to undergo imaging scans with no sedation.