Physicians who stand to gain financially from nuclear stress tests or stress echo exams ordered more of the imaging studies for their patients as a follow-up to cardiac interventional procedures, concludes a new study published November 9 in the Journal of the American Medical Association.

The research could offer support for opponents of physician self-referral, in which nonradiologist physicians operate imaging equipment in their own offices. The study drew a note of caution in an accompanying editorial, however, co-authored by a cardiologist and a urologist, who suggested that the study's conclusions might be off-target.

The study team from Duke University and United Healthcare found that the adjusted odds ratio (OR) of nuclear stress testing among patients treated by physicians who billed for nuclear stress exams was 2.3 for physicians receiving professional and technical fees and 1.6 for those receiving professional fees only, compared to patients whose physicians who did not bill for the tests.

The difference was even greater for stress echocardiography, where the adjusted OR was 12.8 for patients of physicians billing for the professional and technical components and 7.1 for doctors billing for only the professional component, compared to patients whose physicians had no financial incentive to order the tests (JAMA, November 9, 2011).

Even though current practice guidelines "do not recommend routine use of early stress testing following coronary revascularization, we found that 12% of patients with a cardiac-related outpatient visit at least three months after revascularization underwent a stress test within 30 days of their visit," wrote Duke University's Dr. Bimal Shah and colleagues. "We also found that patients treated by practices who billed for the technical and professional fees were significantly more likely to order nuclear stress imaging after revascularization relative to those who did not directly bill for these tests."

Shah and colleagues aimed to examine the association of physician billing and nuclear stress and stress echocardiography following coronary revascularization. Using data from a national health insurance carrier, they identified 17,847 patients between 2004 and 2007 who had both coronary revascularization and a cardiac outpatient visit more than 90 days after the procedure.

The study team then classified the patients' physicians as billing for both technical (practice/equipment) and professional (supervision/interpretation) fees for the study, billing for professional fees only, or not billing for either.

In all, the authors identified 25,557 patients with complete claims data who underwent percutaneous coronary interventions (PCIs) or coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) surgery during the three years preceding June 30, 2007, and who also had an index cardiac-related outpatient visit more than 90 days after their index revascularization procedure.

After excluding patients who had an intervening coronary event or were treated by other specialties, the final study population was 17,847 patients (mean age, 54.6 years). In all, nuclear or echocardiography stress testing within 30 days of the index cardiac-related outpatient visit occurred in 12.2% (95% confidence interval [CI]: 11.8%-12.7%) of cases, Shah and colleagues wrote.

Within that total, the cumulative incidence of nuclear stress testing was as follows:

- 12.6% (95% CI: 12.0%-13.2%) among physicians who billed for technical and professional fees

- 8.8% (95% CI: 7.5%-10.2%) among physicians who billed professional fees only

- 5.0% (95% CI: 4.4%-5.7%) among physicians who billed neither technical nor professional fees

The cumulative incidence of stress echocardiography testing was as follows:

- 2.8% (95% CI: 2.5%-3.2%) among physicians who billed for both technical and professional fees

- 1.4% (95% CI: 1.0%-1.9%) among physicians who billed professional fees only

- 0.4% (95% CI: 0.3%-0.6%) among physicians who billed neither technical nor professional fees (p < 0.001 for both tests)

"Fourteen percent of the study population had symptoms of chest pain, angina, or shortness of breath as the indication for the index visit, whereas 86% did not have a billing diagnosis of symptoms at the index visit," Shah and colleagues wrote.

Under scrutiny

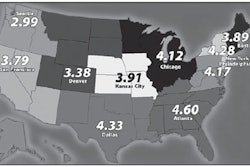

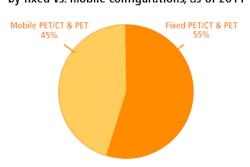

Cardiac imaging has been under scrutiny in recent years as utilization has grown in parallel with a shift from radiology departments into cardiologists' offices. The volume of nuclear perfusion studies occurring in cardiologists' offices rose by 215% between 1998 and 2006, while the rate increased 32% for studies occurring in radiology practices and 181% for studies occurring in other physicians' offices, the authors noted.

One previous study found that physicians who self-referred were more likely to perform imaging tests compared to radiologists or other physicians from different specialties. Another found that self-employed urologists with in-office imaging equipment were two to five times more likely to order imaging tests for a variety of urinary conditions than urologists in employment-based practice models without incentives to scan.

"However, unlike prior studies, we focused specifically on the relationship between the financial billing status of the referring physician and subsequent testing," Shah and colleagues wrote.

The American College of Cardiology Foundation's appropriate use criteria (ACCF AUC) help guide clinicians in deciding when to choose cardiac stress testing with the goal of narrowing variation in care among different clinicians and practices, the authors wrote.

"Our study highlights the need for application of the ACCF AUC in clinical practice and augments findings of other studies that have explicitly examined application of ACCF AUC for nuclear stress and stress echocardiography," they wrote. "Discretionary stress testing after revascularization has potential financial and clinical disadvantages for patients, including the costs of the tests, the exposure to ionizing radiation, as well as potential downstream costs, and consequences from following up false-positive test results."

Criticism

In response, two University of Michigan physicians, urologist Dr. Brent Hollenbeck and cardiologist Dr. Brahmajee Nallamothu, argued in an accompanying editorial that while the research highlights the risks of in-office imaging, an overall increase in imaging use accompanies a broader -- and largely positive -- trend toward outpatient care for cardiology that has accompanied substantial declines in deaths from coronary disease.

"The increase may not entirely be a bad thing," said Hollenbeck in a statement accompanying the editorial. "Office-based imaging offers a number of potential advantages that may improve patient care and satisfaction. There is an opportunity for earlier diagnosis by a physician who is directly involved in patient care. And for specialty care, a one-stop approach can provide enhanced patient access to therapeutic and diagnostic services along with cost-saving efficiencies for the provider."