AuntMinnie.com is pleased to present Part III of our three-part series, Turf Wars in Radiology.

No turf war is easy. But when you’re playing catch-up against a well-equipped, politically potent adversary, it’s downright grim.

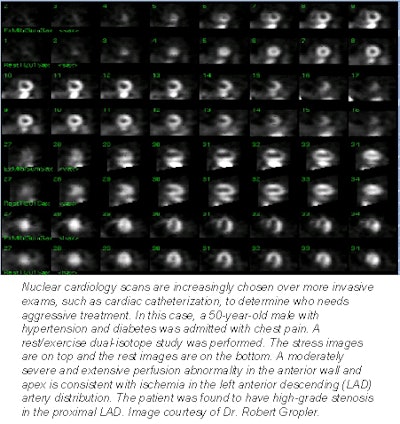

Such are the prospects radiologists face in the burgeoning field of nuclear cardiology. On the plus side, procedures such as myocardial perfusion imaging are increasingly used as cost-cutting gatekeeper exams that differentiate patients who need aggressive and expensive treatment from those who don’t.

Considering that the American Heart Association predicts the cost of cardiovascular disease and stroke will top $298 billion in 2001, such tests will likely be in demand. Unfortunately, thanks to cardiologists’ ever-advancing takeover of the discipline, it’s unclear how much of this work will fall into radiologists’ hands.

Take a look at what radiologists are up against: Number one is time, or lack of it. According to Dr. Daniel Berman, director of nuclear cardiology at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles, radiologists are so busy conducting so many different procedures that they can’t focus specifically on nuclear cardiology.

This means that some radiologists produce nuclear cardiology studies that fail to directly and accurately answer the referring cardiologist’s questions, and fail to consider the patient’s history in the accompanying report. And when cardiologists see this over and over again, they’ll inevitably believe they can perform the studies better than radiologists, he said.

"If, from the start, radiologists had produced superb, high-level work, it wouldn’t have become the problem for them as it has," Berman said.

The siphoning of self-referral

The problem he’s referring to is one of the largest growth areas in nuclear medicine: the proliferation of gamma cameras in cardiologists’ offices. Call it what you will -- self-referral, monopolizing -- but an increasing number of nuclear cardiology work is never referred to hospital-based nuclear imaging centers where radiologists can at least compete with cardiologists for the work. Instead, it stays in cardiologists’ offices.

The extent to which this referral pattern siphons patients away from radiologists was examined by Thomas Jefferson University researchers last year. After analyzing Medicare data for several cardiac nuclear imaging procedures from 1996 to 1998, they determined that the percentage of scans conducted by radiologists dropped from 45% to 37%. Cardiologists, meanwhile, enjoyed a commensurate jump in the percentage of scans from 47% to 55%.

"We found the biggest reason for this change was due to an increase in the number of procedures conducted in a private outpatient setting," said Dr. Charles Intenzo, director of nuclear medicine at Thomas Jefferson University Hospital in Philadelphia. "And since a lot of scans are conducted by cardiologists in their offices, you can conclude self-referral is involved."

Not only are radiologists losing their dominance in the subspecialty, they are also losing revenue. A myocardial perfusion scan, for example, has a technical fee for the isotope, a technical fee for the instrumentation, and a technical fee for the cardiologist’s interpretation of the EKG, which adds up to between $1,600 and $1,800 per scan, Intenzo said.

And radiologists fare no better in hospitals. Some cardiologists use their clout as admitting physicians to ensure that nuclear imaging remains in their hands. According to Dr. Robert J. Gropler, director of the cardiac stress laboratory and nuclear cardiology at Washington University in St. Louis, cardiologists may propose to hospital administrators that either they alone read nuclear cardiology studies -- or they’ll take their patients elsewhere.

"This is a too-frequent and unfortunate strategy," Gropler said. "Cardiologists may have legitimate quality control concerns in doing this, but sometimes they’re also driven by dollars."

So either cardiologists image patients in their offices, or they use their fiscal muscle to preside over nuclear imaging in hospitals. Either way, radiologists and nuclear medicine physicians, who depend on referring physicians for their lifeblood, are left out.

Interpretation and assessment

There is hope, however. According to Berman, nuclear cardiology will continue to grow in clinical importance and utilization, meaning it’s not too late to stake a claim.

In a 1999/2000 survey conducted by Des Plaines, Illinois-based IMV Medical Information Division, cardiac perfusion procedure volume grew from 5.2 million in 1997 to 6.5 million in 1999, representing a 25% increase. So radiologists who are proficient in nuclear cardiology most likely have a booming practice, Berman said.

|

The best advice for those radiologists trying to catch up, then, is to ensure that the acquisition, interpretation, and report of their nuclear scans are on par with what a cardiologist can offer, Gropler said. For radiologists well versed in the instrumentation and physics of imaging, acquisition isn’t a problem, and is often better than what cardiologists can do. But when it comes to understanding the pathophysiology of a scan and the clinical ramifications of their interpretation, many radiologists are lacking, Gropler said.

As Gropler sees it, if radiologists want to keep the business, they must become fluent in both interpreting scans and assessing patient risk in conjunction with information culled from more conventional tests such as EKGs. But is this realistic? Gropler thinks so.

"Radiologists are delving into oncologic PET, which is very difficult to interpret and learn," Gropler said. "So they can learn nuclear cardiology if they want to. The difference is, there’s no PET competitor on the horizon, so they feel it’s an area they can grow into. But the constant competition with cardiology has made nuclear cardiology less attractive to a lot of radiologists."

And competition aside, nuclear cardiology is still imaging. Although a healthy knowledge of cardiology is required, the technologies and techniques involved straddle several specialties.

"There's nothing about cardiac nuclear medicine that precludes a radiologist or nuclear medicine physician from performing it well if they choose to," said Dr. Barry A. Siegel, director of the division of nuclear medicine at the Mallinckrodt Institute of Radiology at Washington University Medical Center in St. Louis. "And because radiologists have a broader experience in nuclear medicine imaging, they are more likely to have encountered a spectrum of imaging problems and are therefore more likely to recognize when artifacts are introduced into images."

Perhaps because of this, not all radiologists are willing to relinquish nuclear cardiology just yet. When Intenzo presented his aforementioned utilization study at the 2000 Radiological Society of North America meeting, the audience members were surprised, some even angry, he said.

It’s impossible to determine what became of their consternation once they left Chicago, but if the membership of the American Society of Nuclear Cardiology is any indication, some radiologists have been spurred into action. The society was founded in 1993 to ensure both quality training and clinical utilization of nuclear cardiology procedures. Its 2,733 U.S. members and 593 international members comprise a mix of cardiologists, nuclear medicine physicians -- and radiologists.

This kind of hands-on interest will produce dividends. As Berman puts it, if radiologists pay attention and do it well, they can continue to participate in nuclear cardiology, particularly in the hospital setting. Siegel also agrees that nuclear cardiology hasn’t yet become a single-specialty discipline.

"Both cardiologists and radiologists can produce incredibly good cardiac nuclear imaging, but there's real garbage from both sides too," Siegel said. "In the final analysis, it's not the card you carry that determines whether you do a good job, it's whether you do a good job, period."

By Dan KrotzAuntMinnie.com contributing writer

August 31, 2001

Related Reading

Turf Wars in Radiology, Part I: Rads, attendings duke it out in the ER, August 10, 2001

Radiology's raided turf: three views from the field, March 20, 2001

Copyright © 2001 AuntMinnie.com