CHICAGO - PET imaging with F-18 fluoroestradiol (FES) radiotracer is on the cutting edge of developing new therapies for breast cancer, according to a June 25 talk at the Society of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging (SNMMI) annual meeting.

Systemic therapy for the disease has been enhanced by the recognition in recent years that breast cancer is not really a single disease, but a disease of several subtypes, explained David Mankoff, MD, PhD, a professor of research radiology at the University of Pennsylvania.

"The picking of systemic therapy used to be a very short discussion," Mankoff said, in the society's annual Henry M. Wagner lecture. "Now sometimes that can take 10 or more minutes per patient just to figure out what the treatment is. Is this something that nuclear medicine and molecular imaging can help with? You bet."

Among breast cancer subtypes are those that express estrogen receptor (ER-positive) and are often therefore dependent upon estrogens for tumor growth. In May, FES-PET (Cerianna, GE HealthCare) was included in the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines for imaging breast cancer in women with ER-positive cases, Mankoff noted.

Mankoff said there are three primary ways FES-PET can help oncologists pick treatments, which have grown since 2012 to include not just new chemotherapy approaches, but monoclonal antibodies such as pertuzumab and trastuzumab that attack the disease in a target-specific way.

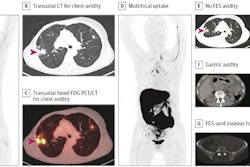

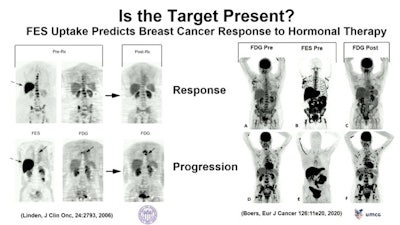

PET scans with an F-18 FES-PET radiotracer can reveal the target for therapy, as well as whether the therapy is working in patients with HER2-positive breast cancer. Image courtesy of David Mankoff, MD, PhD.

PET scans with an F-18 FES-PET radiotracer can reveal the target for therapy, as well as whether the therapy is working in patients with HER2-positive breast cancer. Image courtesy of David Mankoff, MD, PhD.The first role PET plays is helping to determine whether the cancer target is present.

"If we're giving targeted therapy and the target's not present, it's very unlikely that that therapy's going to work," he said.

Number two is determining whether the drug selected actually reaches the target, Mankoff said.

"This is something that's very difficult to do without imaging and is a very important part of what we offer the patient," he said.

Finally, PET imaging can help doctors determine whether there has been a pharmacodynamic response, which refers to the relationship between the concentration of the drug at the site of action and any resulting effects or adverse effects.

One challenge using PET imaging with targeted tracers like FES is determining how homogenous the cancer may be, Mankoff added. In other words, the approach may not visualize differences between tumors of the same type in different patients. In this regard, he said that dual imaging with F-18 FES and FDG, a standard and more general imaging tracer, may be effective, he said.

"This paired imaging with FDG and FES I think is critical," he said.

Ultimately, the future does not get simpler, Mankoff noted. New targets are being identified in breast cancer, including genomic and immunologic targets, and these will also lead to the development of new drugs and new PET imaging approaches for monitoring their use in patients, he said.

"It's a little bit uncertain about what the future holds, but there is one certainty in my mind -- that is that molecular imaging teamed with chemists, physicists, biologists, and clinicians is here to stay and really well poised to be able to take on the level of complexity that our oncologists and other cancer-treating doctors have to take," Mankoff concluded.