PET imaging shows that military instructors exposed to repeated blast episodes have abnormal brain pathology typically associated with Alzheimer's disease, according to a study published May 8 in Radiology.

A group led by Dr. Carlos Leiva-Salinas, PhD, of the University of Missouri in Columbia, identified beta-amyloid deposits on brain PET scans in healthy adult men (military instructors) exposed to mild repetitive subconcussive injuries. The finding elucidates brain changes that could drive dementia in patients with traumatic brain injury (TBI), the authors suggested.

"Amyloid accumulation in patients with TBI suggests a relationship between traumatic injury and the establishment of neuropathologic features of dementia," the group wrote.

TBI can be the result of direct head trauma, but it can also result from indirect forces such as shockwaves from battlefield explosions that shake the brain violently in the skull, the authors explained. While previous autopsy studies have shown amyloid plaque deposits -- a hallmark of Alzheimer's disease -- as early as hours after severe brain injury, few PET studies have explored these associations in active patients.

To further elucidate these connections, the researchers recruited nine healthy military grenade or breacher instructors about to begin duties at Fort Leonard Wood Military Base in Fort Leonard, Missouri, from January 2020 to December 2021. These officers train recruits in the use of hand grenades and explosives to force open doors.

All instructors underwent baseline F-18 florbetapir PET scans and again five months after being exposed to repeated blast events during their training duties. Age-matched healthy control participants not exposed to blasts and without a history of brain injury were also evaluated at similar time points.

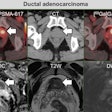

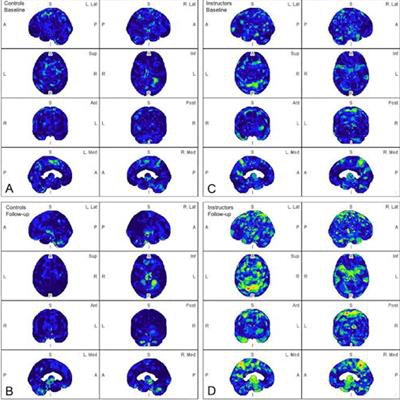

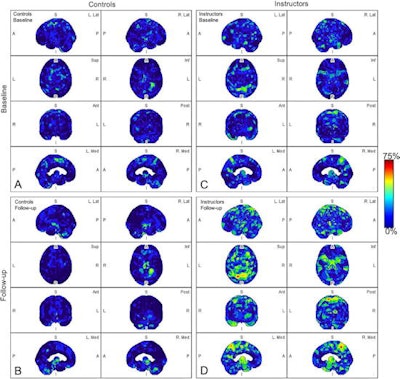

Parametric maps of amyloid deposition in healthy control participants (A and B) and blast-exposed military instructors (C and D) at baseline (A and C) and follow-up (B and D). The blue-to-red scale indicates the frequency of statistically abnormal amyloid uptake in a particular brain voxel. Whereas no abnormal amyloid uptake was identified at baseline or follow-up in healthy control participants (A, B), amyloid deposition occurred most frequently in blast-exposed participants in the superior parietal lobules, precuneus, cingulum, paracentral lobules, and anterior temporal and occipital lobes (D). Image and caption courtesy of Radiology.

Parametric maps of amyloid deposition in healthy control participants (A and B) and blast-exposed military instructors (C and D) at baseline (A and C) and follow-up (B and D). The blue-to-red scale indicates the frequency of statistically abnormal amyloid uptake in a particular brain voxel. Whereas no abnormal amyloid uptake was identified at baseline or follow-up in healthy control participants (A, B), amyloid deposition occurred most frequently in blast-exposed participants in the superior parietal lobules, precuneus, cingulum, paracentral lobules, and anterior temporal and occipital lobes (D). Image and caption courtesy of Radiology.In a comparison between the groups, blast-exposed participants showed significantly increased amyloid deposition in four brain regions known to be abnormal in Alzheimer's disease: the inferomedial frontal lobe, precuneus, anterior cingulum, and superior parietal lobule. Conversely, no amyloid deposits were observed in the control participants.

"We found that most military instructors exposed to blast episodes had abnormal beta-amyloid brain deposition in the early phase after the subconcussive events," the researchers wrote.

Ultimately, acute brain amyloid changes in individuals exposed to subconcussive brain trauma have not been well established previously in the literature, the authors wrote. This study adds to that aim and further supports PET as a diagnostic tool in these patients.

"PET imaging could be used to identify early-stage [beta-amyloid] accumulation in individuals or professions exposed to traumatic brain injury such as military personnel, police officers, firefighters, [or] football players," the group concluded.