Dr. Ashraf Selim was always fascinated by his country's heritage, but he had little idea he would help solve a puzzle that had baffled Egyptologists for nearly a century, or that he would accomplish this in less than 24 hours.

In late 2005, an Egyptian team of radiologists and a group of foreign radiologists were sponsored by National Geographic and Discovery Channel to study CT images of the mummified remains of Tutankhamun. Both teams' goal was to determine what killed the king in 1323 BC, when he was around 19 years old. They had been given three months to analyze the data and write their report, but discrepancies between their interpretations were hindering the conclusion.

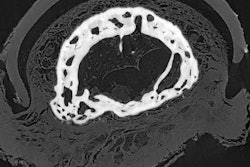

CT showed King Tut had a mild form of club foot compounded by avascular necrosis. All images courtesy of Dr. Ashraf Selim.

CT showed King Tut had a mild form of club foot compounded by avascular necrosis. All images courtesy of Dr. Ashraf Selim.The points of debate were threefold: Why were there two layers of embalming resin and had these been introduced separately or through two routes? Why was there a loose bone in the skull and where it had come from? And how significant was the left femoral supra-condylar fracture and was it inflicted before or after death?

With the three months up and a press conference scheduled for the next day, the then head of Egypt's Supreme Council of Antiquities, Egyptologist Zahi Hawass, PhD, asked Selim, who is professor and head of radiology at Cairo University Hospital, if he could look at the scans to help diagnose the most likely cause of death. Between 3 p.m. and 2 a.m. the following morning, Selim studied the CT images and wrote up his findings, joining the two teams the following day just in time for the press conference.

CT's discoveries

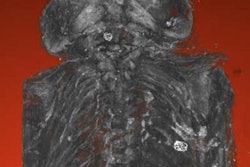

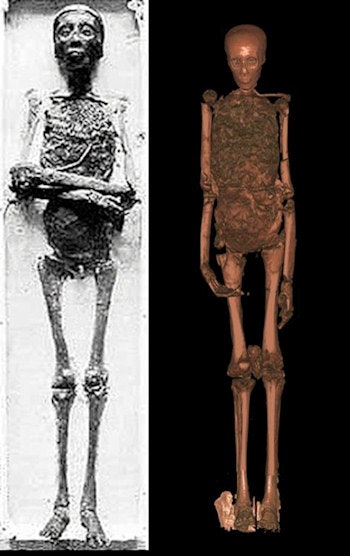

The images, which were produced on a donated Siemens 6-slice CT scanner, revealed the trunk, limbs, and head of Tut's body were separated, and the body was fractured in several areas.

"This probably happened during exhumation," Selim told AuntMinnieEurope.com in a phone interview. "They ruined the body when they removed the heavy golden mask that was stuck to the mummy."

The scans also revealed a supra-condylar femoral fracture just above the knee. While the other fractures were sharp due to the brittle nature of the bones, this fracture had a blurred outline. Furthermore, dense material mimicking embalming fluid had gathered at the outer edges of the fracture.

"This was accompanied with a significant wound, and probably premortal because the liquid resin went through it to the edges of the fracture. As there were no antibiotics at the time, this fracture may have been the underlying cause of death either through embolism or septicemia," he added.

The two teams agreed with Selim on this key radiological point.

Interestingly, when Tutankhamun's body was first examined by x-ray in 1972 and again in 1978, a small piece of bone inside the skull led experts to believe that he had died after a blow to the head. This theory was supported by visualization of a thick dense layer, at the time attributed to bleeding. Modern CT ruled this out. There were no fractures in the skull itself and the dense layer noticed on x-ray proved to be embalming fluid. Selim's further examination of the images showed the loose bone fragment had come from the first cervical vertebrae which was broken, and had entered the head cavity through the hole at the base of the skull.

"Chisels were used to remove the mask and we think that the vertebrae broke and went into the skull at that point. If the injury had been premortal, the bone would not have been loose but would have been stuck within the thick layer of embalming fluid," he noted.

Tutankhamun remained in a wooden crate during the scans. Other than this, the CT exam was conducted as for a live patient, with the machine calculating radiation dose based on size and weight.

Tutankhamun remained in a wooden crate during the scans. Other than this, the CT exam was conducted as for a live patient, with the machine calculating radiation dose based on size and weight.Another curiosity is Tutankhamun is the only mummy so far to show two layers of embalming fluid in the skull.

"Either his head was embalmed twice, at two different times, or at the same time but in different positions. This duplication of the process may have been accidental -- or because Tut's embalmers wanted to take extra care with him," Selim said.

More than 100 walking sticks

More than 100 walking sticks were found in Tutankhamun's tomb when it was explored and cleared between 1922 and 1932. Furthermore, on one wall, a painting of a hunting scene in which Tut holds an arrow while seated, provides an uncommon depiction of a pharaoh. The CT pictures shed light on these riddles, and showed that Tut had a mild form of club foot, a congenital anomaly that later developed avascular necrosis, a common disease in adolescents that causes pain, inflammation, and limping.

DNA results from Tut's remains showed he would have been carrying a severe form of malaria (Plasmodium falciparum). One theory is this disease is what killed him, but given this form of malaria was endemic at the time, the experts concluded this was unlikely.

Other theories have suggested Tut had frontal lobe epilepsy and a related hormone imbalance, based on transcripts of his visions, and allusions to an outwardly feminine physique. Indeed, one suggestion is Tut's fatal injury may have been sustained during such an epileptic seizure.

"The problem is that anyone can say anything, but as scientists we have to look at the concrete evidence. We don't have a brain to study so to suggest epilepsy is not a medical conclusion. One trigger for the suggestion is that the mummified head appears elongated from front to back. However, when measured radiologically the skull is not elongated even if it appears otherwise," Selim said.

The same suggestion of epilepsy and a hormone imbalance which would have influenced the physique had also been said of Tutankhamun's father, Akhenaten. This theory seems to have been largely based on stylized statues of Akhenaten showing him with a slim waist but large hips and lower body, and on descriptions of his own seizure-like episodes and visions.

However, in 2010, Selim was asked to study other members of Tut's family and also had the chance to review Tut's CT images a second time. Tutankhamun's father, mother, and grandfather were scanned on the same 6-slice CT machine. The data were then reconstructed into 3D images for analysis. Selim and his colleagues authored, "Ancestry and pathology of Tutankhamun's family" (Journal of the American Medical Association, 17 February 2010, Vol. 303:7, pp. 638-647) in the same year.

"When we examined CT images of the skeletons, they had normal measurements, with nothing misshapen. So radiologically speaking, there is no evidence of a feminine physique, either in Akhenaten or Tutankhamun," he noted.

Learning from the mummies

Work on the mummies stopped in 2011 due to the political situation. Since then, a succession of different governments has meant the research has been delayed further.

"We have examined most of the royal mummies but want to finish this work, otherwise it will be a loss for Egypt and the whole world," Selim said.

With so much disease to be diagnosed in the living, some might ask, "What good comes of imaging dead people?" However, pointing to specific work on Queen Hatshepsut, Selim believes both scientists and historians can learn a lot from the mummies.

Scientists must look at concrete evidence and not conjecture as a cause of death, according to Dr. Ashraf Selim.

Scientists must look at concrete evidence and not conjecture as a cause of death, according to Dr. Ashraf Selim.Nothing was known about Hatshepsut except she built the biggest temple in the Valley of the Queens. She is thought to have come to the throne around 1478 BC and ruled as pharaoh for 20 years until her death in 1458 BC at the age of 50. Because she was eradicated from most records by her successor, historians were eager to find her body and discover how she died.

Selim described how five mummies were brought to him to be scanned, with the possibility that one of them was Queen Hatshepsut. If it was, the question remained as to which of the five was her. The only clue was a canopic jar bearing her name, and presumably containing her organs. He scanned the jar in 2008 and on the CT image, discovered among the contents a small, very dense structure which when magnified turned out to be a broken molar tooth.

Selim returned to the images of the five mummies and saw that one had damaged teeth. In the upper jaw he found the root of a broken tooth from which the discovered fragment might have originated. Computer software cut and stitched the pictures together and they matched perfectly. Further examination showed that Hatshepsut died of cancer which had spread into her bones, particularly her left iliac bone.

"Egypt was a great civilization, but what made them great? How did they know that the thinnest part of the skull was in the roof of the nose and that it was here that they could push up with a stick to break it and remove the brains during mummification?" he asked. "The Egyptians were knowledgeable, understood many diseases, and performed surgery."

He hopes in the near future, once government approval has been granted for pending projects, the research will help to create a database of the royal mummies, containing information about their family connections, which diseases they suffered from, any treatments that seem to have been carried out -- and why they died.