SINGAPORE - MRI shows promise for helping to diagnose post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), according to a presentation delivered May 7 at the International Society for Magnetic Resonance in Medicine (ISMRM) meeting.

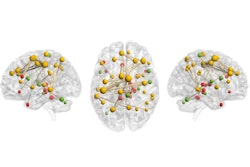

Presenter Osamu Abe, MD, PhD, of the University of Tokyo in Japan offered attendees a primer on the MRI findings that "most robustly" identify the condition, listing hyperactivation of the amygdala and dorsal anterior cingulate cortex, hypoactivation of the ventromedial prefrontal cortex, and atrophy of the hippocampus.

"Neuroimaging is now offering insights into the neurobiological basis for normal [brain] development, aging, and disease processes," Abe noted.

PTSD may occur when an individual is exposed to severe and/or ongoing trauma such as childhood abuse or war, Abe said, and it can have a wide-ranging impact on an individual's behavior, mood, and cognition. He and his team found motivation for the study after the Tokyo subway sarin event in 1995.

"Considering its prevalence, [PTSD] is a significant public health concern," he said. "Terrorism victims and combat veterans are highly susceptible groups."

Symptoms of the condition tend to persist for more than one month after the original traumatic event and can include recurrent, intrusive memories; negative changes in cognition or mood (inability to remember aspects of the trauma, self-blame); increased fear response; reactivity (irritability, impulsivity, hypervigilance); avoidance of trauma-reminders (people, places, events); and sleep disturbances (nightmares, startle reflex).

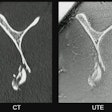

In the past, there have not been particular visual abnormalities on conventional MRI that could help diagnose PTSD. Instead, the condition has been mainly diagnosed via patient interviews with a psychiatrist and/or patient-completed questionnaires. But recent neuroimaging advances such as voxel-based morphometry (VBM) have made MRI an increasingly viable tool for helping to confirm the diagnosis of PTSD and monitor treatment effects, Abe noted.

In particular, the hippocampus in an individual with PTSD tends to have lower volume and decreased levels of N-acetyl aspartate (the latter of which suggests axonal dysfunction or loss) -- findings that can't be accounted for by a history of alcohol abuse or depression, he said. As for the amygdala -- the limbic system structure that manages emotions and memories and is key to threat detection and fear learning -- it tends to manifest in PTSD as exaggerated reactions to trauma-related stimuli, Abe noted.

He listed key findings on MRI for PTSD:

- Hyperactive amygdala and dorsal anterior cingulate cortex (dACC), hypoactive ventromedial prefrontal cortex (vmPFC), and atrophy of the hippocampus.

- Impaired neurocircuits that involve fear learning, threat detection, contextual processing, executive function, and emotional regulation.

- Hypoactive default mode and central executive networks, and an overactive salience network. "The sympathetic nervous system hyperactivity results in hypersensitive threat detection and inefficient modulation of the default mode and central executive networks," Abe said.

MRI can help clinicians identify PTSD, although more development of the modality for this indication is needed, according to Abe.

"Imaging [for PTSD] may be the gold standard someday [for identifying] individuals at high risk [of the condition]," he said.